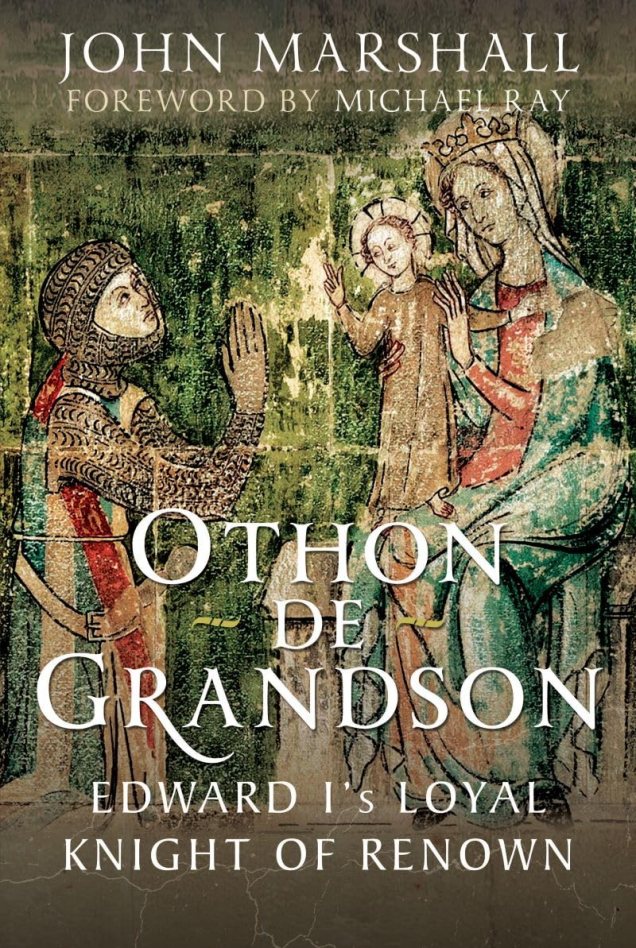

Today, it is a pleasure to welcome John Marshall to History…the Interesting Bits with an article about a very intriguing chap, Othon de Grandson. Othon was a very good friend of Edward I and one who could arguably challenge William Marshal for the title, Greatest Knight. John’s new book is a biography of this remarkable man.

So, over to John…

Othon and the Templars

A question I asked myself in writing Othon de Grandson: Edward I’s Loyal Knight of Renown was exactly what was the Savoyard knight’s relationship with the Knights Templar? The relationship of Edward’s friend and envoy with the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon is a long one and indeed began over a century before he was born.

Othon’s ancestor Barthélémy de Jura, treasurer of Reims, then Bishop of Laon in Picardy, was there at the very beginning of the crusader order. Barthélémy was at the 1128 Council of Troyes, chaired by Bernard of Clairvaulx which ratified the rule of the the Templars. He was a kinsman, through his mother, of Bernard of Clairvaulx, and would later retire as a monk to the Cistercian abbey he helped found at Foigny. Another ancestor was another Barthélémy who took up the cross and joined the Second Crusade. He is reported to have departed this life in Jerusalem in 1158.

So, when Othon de Grandson accompanied his liege the Lord Edward on the ninth crusade in 1271 his family was no stranger to crusading.

But the story of Othon de Grandson’s close association with the Templars begins in earnest with his flight from Acre accompanying Templar knight Jacques de Molay in 1291. Grandson had likely been sent to Acre in 1290 as preparation for a crusade by King Edward I that never came to pass. They were all overtaken by Al Ashraf Khalil, the sultan of Egypt who successfully led a Mamluk assault on the last crusader outpost in Outremer. King Henry II of Cyprus, the gravely wounded Master of the Hospitallers Jean de Villiers, the soon-to-be Master of the Templars, Jacques de Molay and Othon de Grandson washed up on the shore of Cyprus as refugees from Acre. The Templars were in need of a new Grand Master, and it is said that Othon de Grandson was “involved” in the election of Jacques de Molay.

The idea of being ‘involved’ came from a declaration given later during the suppression of the order; a Templar, Hugh de Fauro, gave testimony that Jacques de Molay had sworn before the Master of the Hospital and ‘coram domino Odone de Grandisono milite’ that is ‘before the knight Sir Othon de Grandson.’ We then hear from Hethum of Corycus that Grandson and Jacques de Molay, had had a hand in affairs and the better reordering of the kingdom of Cillician Armenia to meet the Mamluk threat and preserve it as a base for ongoing crusading ventures. Grandson’s relationship with Molay and the Templars does seem to stem from this time at Acre, on Cyprus and in Armenian Cilicia between 1291 and 1294.

We then meet the financial entanglement of grandson with the Templars. Evidence of this comes not only from payments from the Templars to Grandson but also grants in the other direction. When both Molay and Grandson were back in the west, on 14 July 1296, Othon would grant the Templars 200 Livres from his salt revenues at Salins-les-Bains in the Franche Comté, a source of revenue he had used to similarly grant the monks of Saint-Jean Baptiste in Grandson before he had left for the

Holy Land. The first grant was in essence for prayers of safe return; the second grant looks like thanks for a safe return. The great salt works of Salins belonged to the Count of Burgundy; they were also known as the Seigneurs de Salins, and the works and its grander enlightenment era equivalent today enjoy UNESCO-listed status. The grant to the Templars was in consideration of the great help Othon had received from ‘mes chiers amis en dieu freres Jaques de Molai’, that is, ‘my dear friend in God brother Jacques de Molay’ and he referred to the help which ‘li freres du celle meismes Relegion ont fait a mes accessors, e a moi deca mer et de la mer en la sainte terre e ne cesse encore de faire’ or ‘the brethren of that same order have given to my ancestors and to myself in the West and in the East in the Holy Land, and still continue to give’. His reference to his anccessurs is likely to mean Barthélémy de Grandson who had, as we saw, died in 1158 in Jerusalem.

The reverse Templar ongoing and enormous financial commitment to Grandson is confirmed to us in a papal confirmation of 17 August 1308 by Pope Clement V. Upon suppression of the order Grandson was keen, obviously, that Templar payments continue, since they were the tremendous annual sum of 2,000 Livres Tournois, equating to £500 at the time, and over £350,000 in today’s money. The pension arrangement was made by a Grand Master, named as Jacques de Molay, and variously dated to 1277, 1287 or 1296–97. French Templar historian Alain Demurger wrote: ‘Fault lay with the editor of Clement V’s records … The editor put the date 1277, while M. L. Bulst-Thiele transcribed it as 1297, whereas the original, very clearly and without abbreviations or deletions says 1287.’ In his notes to this assertion, he cites the Vatican Archives date as ‘Anno millesimo duecentesimo octuagesimo septimo’ or ‘In the year one thousand two hundred and eighty-seven.’

Now of course Molay did not succeed Beaujeu until 1292, which renders the dating of the award problematic. Demurger suggested that it was not Molay who made the award despite specific reference to him ‘Jacobus de Mollay’, but his predecessor Beaujeu – in short, that the date was correct but the master’s name incorrect. Alan Forey argued the contrary, writing that it was: ‘more likely that the grant was made by James of Molay and that the date was wrongly copied’. Given, Molay’s 1292 election as Grand Master this would suggest 1296–97 – in short, the date was incorrect, but the master’s name correct. Demurger acknowledged in his notes that ‘a new problem arose … Grandson and the Temple were already connected in 1287: where, how and for what reason?’ Indeed, Demurger’s dating would create such questions, while Forey’s dating would place them squarely in the context of the Fall of Acre and his time in the east with Molay. This ‘compensare’ was given by the The Templars for ‘operibus virtuosis’ or ‘virtuous actions’ rendered by Othon in support of the order, but surely more likely post-Fall of Acre than before.

In confirmation of the pension, Clement V granted Othon three former Templar houses in France as a part of the continuing settlement, those at Thors, Épailly and Coulours, an act unlikely to have been undertaken at the time in favour of a knight of the order. And so, the ‘virtuous works’ referred to by Pope Clement would appear to date from Grandson’s time in Acre in 1291. So, the date of 1277 attached to the payments by the transcription of them is certainly mistaken, and for the 1287 dating of the original 1308 manuscript we should read 1296–97. Demurger gives 1296 clearly as the date for Molay meeting with Grandson in Paris and the Salins grant. Othon de Grandson’s intimate links with the Templars continue to intrigue, but in Cyprus and Armenia 1292-4, as at Acre in 1291, and here with his pension payments they point to a significant and close ally in matters Outremer rather than a member of the order itself, of which there is no mention.

Grandson, was a close friend of the Templars, having fought alongside them at Acre in 1291, been there in Cyprus as a part of Molay’s election as Grand Master, and in receipt of a handsome annual pension from the order. So, at Philippe ke Bel’s suppression of the order and Molay’s arrest and the rumours swirling around France, the scandal would have touched directly upon him. But at no point can we find Grandson implicated in events, other than petitioning Pope Clement for the maintenance of his pension. But nowhere too can we find him leaping to the defence of Molay, his former friend and ally, at least not in a way that has left any trace. As Demurger said in conversation with the author of this book, Grandson did not try to defend Molay. A character flaw? Demurger went to affirm that one cannot speculate about possible motives, Grandson was by now seventy years of age, had discretion become the greater part of valour?

It is because of his avoidance of implication in the suppression of the Templars, that despite his Templar connections, we can be as certain as certain can be that Othon de Grandson was a friend, ally, indeed fellow traveller of the Templars, but not actually a member of the doomed order, As Alain Demurger said unequivocally to the question, was Grandson a Templar? – Non. What were the enormous payments from the Templars to Othon de Grandson for? What were the “operibus virtuosis”? It’s only speculation but what did Grandson have that might be valuable to the Order? – access better than anyone to Edward I’s ear and access to the English court.

*

About the Book:

There were once two little boys – they met when they were both quite young; one was born in what’s now Switzerland, by Lake de Neuchâtel, his name Othon de Grandson, and the other was born in London, his name Prince Edward, son of King Henry the third of that name. Othon was probably born in 1238, and Edward, we know, in June 1239. These two little boys grew up and had adventures together. They took the cross together, the ninth crusade in 1271 and 1272. Othon reputedly sucking poison from Edward when the latter was attacked by an assassin. In 1277 and 1278, they fought the First Welsh War against the House of Gwynedd, Othon doing much to negotiate the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1278, which ended hostilities. When war broke out again in 1282 they fought the Second Welsh War together. Othon led Edward’s army across the Bridge of Boats from Anglesey and was the first to sight the future sites of castles at Caernarfon and Harlech. Edward made his friend the first Justiciar (Viceroy) of North Wales. When Edward and Othon went to Gascony in 1287, Othon stayed in Zaragoza as a hostage for Edward’s good intentions between Gascony and Castille. Later, in 1291, when Acre was threatened by the Mamluks, Edward sent Othon as head of the English delegation of knights. When Acre finally fell to the Mamluks bringing the Crusades to a close, who was the last knight onto the boats? Othon de Grandson, helping his old friend, the wounded Jean de Grailly onto the boat. When Othon returned from the East, he found England at war with Scotland and France; he would spend his last years in Edward’s service building alliances and negotiating peace before retiring to his home in what is now Switzerland after the king’s death in 1307. Grandson lived in the time of Marco Polo, Giotto, Dante, Robert the Bruce, and the last Templars. He was right there at the centre of the action in two crusades: war with Wales, Scotland, and France, the Sicilian Vespers, and suppression of the Templars; he walked with a succession of kings and popes, a knight of great renown. This is his story.

Othon de Grandson: Edward I’s Loyal Knight of Renown is available now from Amazon.

About the Author:

Having moved to Switzerland, and qualified as a historian (Masters, Northumbria University, 2016), the author came across the story of the Savoyards in England and engaged in this important history research project. He founded the Association pour l’histoire médiévale Anglo Savoyards. Writer of Welsh Castle Builders: The Savoyard Style and Peter of Savoy: The Little Charlemagne both available from Pen and Sword Books Ltd. Member of the Henry III Roundtable with Darren Baker, Huw Ridgeway and Michael Ray.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

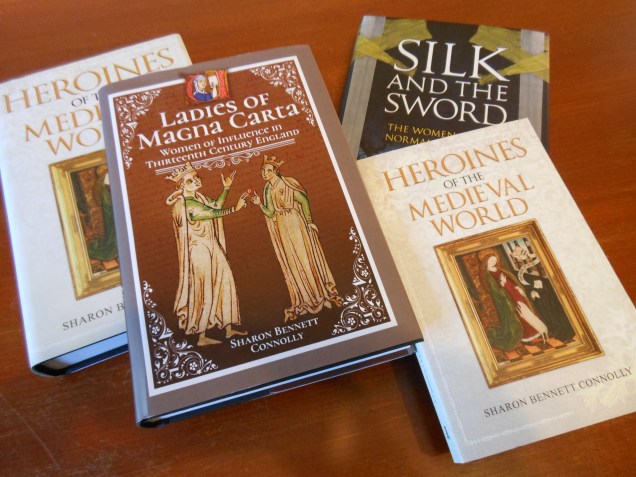

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS and John Marshall