Born in 1499, Diane de Poitiers was the widow of Louis de Brézé, Grand-Sénéschal of Normandy, 39 years her senior and a grandson of King Charles VII by his mistress, Agnes Sorèl; he was also reputedly the ugliest man in France. Diane de Poitiers had joined the court at the age of 14 and had married to Louis de Brézé, a rich and powerful widower, the following year. An attractive young woman, Diane had a natural elegance and was careful of her looks. She never used make-up to enhance her appearance, using only cold water on her face and body; she went to bed early and took regular outdoor exercise, avoiding excesses of any sort. When she came to court, Diane was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Claude of France. When Claude died, she served Francis I’s mother, Louise de Savoie and the Queen Eleanor of Austria, King Francis’ second wife. Widowed in 1531, Diane wore black and white – the colour of mourning – for the rest of her life, and she retained control of her husband’s finances, the king allowing her to manage all her inherited estates without the supervision of a male guardian or relative, thus allowing Diane to be financially independent.

The younger son of Francis I and Queen Claude, Henri had spent 4 years in captivity in Spain from the age of 7. Following Francis I’s defeat at the Battle of Pavia in 1525, in order to obtain his own freedom, the French king had agreed to give up his 2 sons, Henri and his older brother, Francis, as hostages and had them despatched to captivity in Madrid. It was, perhaps, not surprising that Henri had returned from his four years in Spain at the age of eleven ‘an unpolished and silent boy.’1 The king asked Diane de Poitiers to become his son’s tutor. She and the prince developed a strong bond which would eventually develop into a romantic relationship, despite the fact she was 19 years older than Henri.

In 1533, Henri was married to Catherine de Medici and a year later, Diane became one of his mistresses. And in 1536, at the age of 18, Henri’s older brother, Francis, died suddenly, making the young prince dauphin of France. Two years later, Henri fathered a daughter on another mistress, Filipa Duci, who was the sister of one of his Piedmontese grooms. The baby girl was named Diane de France, in tribute to Henri’s favourite mistress. With his marriage to Catherine de Medici still childless, the birth of an illegitimate daughter was proof, as far as Henri was concerned, that the fault did not lay with him. It was, however, a humiliation for Catherine.

Once Henri became dauphin, the apparent barrenness of the prince and his wife became a serious concern. Talk at court began to centre around the possible repudiation of Catherine. Diane and Catherine, mistress and wife, formed a truce in order to ward off any attempts to force Henri and Catherine to divorce; concerned that Catherine was failing in her duty to produce an heir and that, although Henri liked Catherine well enough, he was not passionate with her. Aware that her own position would be threatened by the arrival of a new bride for Henri, Diane determined to help Catherine. To resolve the situation, Diane offered the dauphine advice on Henri’s preferred sexual positions and how to arouse the prince’s passion. Awkward! When this did not work, Catherine had spy holes made in her chamber floor so that she could watch Henri, in the chamber below, with Diane. Historian Estelle Paranque explains that; ‘the sight of their intimate encounter only succeeded in deeply hurting the dauphine, however, who realised that Henri did not perform the sexual act the same way with her as he did with his mistress.’2

Diane continued to offer advice to Catherine, before eventually offering to stimulate the prince before sending him to his wife’s bedchamber. However awkward this must have been for both women, it apparently worked, with Catherine herself admitting to Henri showing more passion in their lovemaking. And by June 1543, Catherine was pregnant. A baby boy arrived on 19 January 1544, named Francis after his grandfather. And a year later, a baby girl named Elisabeth joined the little prince in the nursery. Catherine was finally able to feel safe from being discarded and abandoned. Ten children eventually filled the royal nursery, seven of whom reached adulthood.

In the autumn of 1544, probably somewhat to Catherine’s satisfaction, King Francis’ mistress, the duchesse d’Étampes, with whom Diane had a bitter rivalry, succeeded in arranging her banishment from court, after Henri had replaced one of the duchess’s protégés while campaigning against the English in Picardy. Diane retreated to her château at Anet, closely followed by a sulking Henri. She received permission to return to court the following year.

In spite of this, Catherine would remain in the shadow of Henri and Diane’s love throughout their marriage, with Henri continuing to shower his favourite mistress with patronage. He even had a monogram designed, interlacing the H and D of their names, and placed them everywhere he could. King Francis I died in 1547, and Henri was now King Henri II of France. But, while Catherine was now queen of France, she wielded little political influence and it was Diane’s star that rose still higher. She was made maitresse en titre and a permanent member of Henri’s privy council. She was showered with jewels and offices, as well as estates and other honours. The Venetian ambassador, Marino Cavalli noted Diane’s influence over the new king, stating that ‘this lady has made sure to indoctrinate, to correct, and counsel’ Henri.3 Wherever the king and queen were found, so too was Diane de Poitiers, walking right behind Catherine. In Paris, Diane was named in the same rank as the princesses of France, while in Rouen the aldermen brought her jewels and gifts made of gold and laid them at her feet. King Henri gave her the royal Château of Chenonceau, despite the protestations of Catherine, who thought it should be hers. Henri ignored Catherine’s pleas. Yet another slight the young queen had to endure due to her husband’s infatuation with Diane de Poitiers.

And it was to Diane that the responsibility of impressing foreign ambassadors fell. In 1550 the English ambassador, William Pickering, was staying at the French court, at that time at Diane’s Château of Anet. After his audience with the king, Diane entertained the ambassador, showing him the magnificence of her château. And in 1552, Venetian ambassador Lorenzo Contarini remarked on Diane’s influence at court; ‘she knows about everything and every single day, after dinner, the king looks for her and spends an hour and a half with her to discuss everything that has happened.’4 At tournaments, it was Diane’s colours that the king displayed, not those of his queen. Created Duchess of Valentinois by Henri II, she was, quite literally, the love of his life. Although the king never had children with his maitresse en titre, he did have children with other mistresses and, of course, his wife.

As Henri’s reign progressed, he began to show greater confidence in his queen, but Diane still managed to thwart the Catherine achieving significant power. In 1548 and in 1552, when Henri was out of the country on campaign, he entrusted Catherine with the regency of France. However, in 1548 Diane managed to persuade Henri to appoint Anne de Montmorency (a man) as co-regent and in 1552, she had Chancellor Bertrandi named as co-regent, effectively forcing Catherine to answer to him.

Catherine would, eventually get the upper hand.

The rivalry between Catherine de Medici and Diane de Poitiers would come to an abrupt end in the summer of 1559. In the March of that year, Henri had turned 40. He had spent the last 26 years of his life married to Catherine de Medici; for 25 of those years, he had been in love with Diane de Poitiers. On 22 June, Catherine and Henri’s daughter, Elisabeth, was married to Philip II, King of Spain, by proxy in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. The wedding was followed by a series of celebratory tournaments. In 1552, Catherine had been warned by Simeoni, the famous astrologer, that Henri would die in a duel in his 40th year, and that the wound would first blind him. This knowledge made a superstitious Catherine quite anxious as the jousts started. However, the king was always eager to impress his mistress with his prowess in the lists, wearing her colours of black and white. The king performed admirably against his first opponent, winning when he hit his brother-in-law, the duke of Savoy, in the chest and unhorsed him. The second bout was a draw, and it was after this that Catherine asked him to retire, but Diane de Poitiers encouraged the king to continue and in the next joust, though unhurt, Henri fell off his horse. The king insisted on going again, against the same opponent, Gabriel de Montgomery, and it was at this moment that King Henri II’s luck ran out.

Montgomery’s lance struck the king’s helmet, a fragment of the splintered lance having pierced Henri’s eye. Henri had fallen from his horse, and as his squires removed his helmet they revealed a face covered in blood. The mortally wounded king was carried to his chambers and placed in his bed, joined by Diane and Catherine, one at either side, both sobbing. Catherine called the renowned surgeon Ambroise Paré to attend the king, but after practicing the required surgery on executed prisoners, Paré had to tell the queen that the king could not be saved. Henri II lingered for 10 days, in agonising pain, before dying on 10 July 1559. He had been attended throughout by his queen. Henri is said to have called out for Diane, but she was not allowed to see him, nor attend the funeral. Diane was banished from court. Her influence ended with the king’s death and power now rested firmly in the hands of Queen Catherine, mother and regent to the new king, Francis II.

On hearing of Henri’s death, Diane wrote to Catherine asking for ‘pardon for my past offences against your person’ and signing the letter ‘your most obedient and loyal subject.’5 Diane sent back some crown jewels, items that had been gifted to her by Henri, in the hope that the queen would be compassionate. Diane de Poitiers knew that without the king’s protection, she was vulnerable to Catherine’s malice. The queen was not spiteful, however, and allowed Diane to keep all that she had acquired in her years at court. Except for the Château of Chenonceau. Diane retreated to her château at Anet, where she had once entertained ambassadors and lived there, a virtual exile. She would die there in 1566, following a fall from her horse the year before. For a quarter of a century, Diane de Poitiers had enjoyed more influence as the king’s mistress than any other woman in France, including the queen. Henri II had showered affection, riches and power on the woman who had held his heart, choosing to ignore the humiliations that he was heaping upon his wife.

The scandalous ménage-a-trois only ended with the king’s death.

*

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Notes:

1. Leonie Frieda, Catherine de Medici; 2. Estelle Paranque, Blood, Fire & Gold; 3. ibid; 4. ibid; 5. ibid

Select Bibliography:

Leonie Frieda, Catherine de Medici: A Biography; Estelle Paranque, Blood, Fire & Gold: The Story of Elizabeth I and Catherine de Medici; Jill Armitage, Four Queens and a Countess: Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Lady Jane Grey and Bess of Hardwick; Amy Licence, In Bed with the Tudors; Amy Licence, The Sixteenth Century in 100 Women; Erin Lawless, Forgotten Royal Women: The King and I; Estelle Paranque, ‘The French Royal Mistresses who made it about more than sex’, historyextra.com; Susan Abernethy, ‘Claude de Valois, Queen of France,’ thefreelancehistorywriter.com; ‘Queen Claude of France’ Royal Armouries.org; Sylvia Barbara Soberton, ‘Claude de France: Anne Boleyn’s Mistress,’ onthetudortrail.com; Goldstone, Nancy, The Rival Queens: Catherine de Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois and the Betrayal that Ignited a Kingdom

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

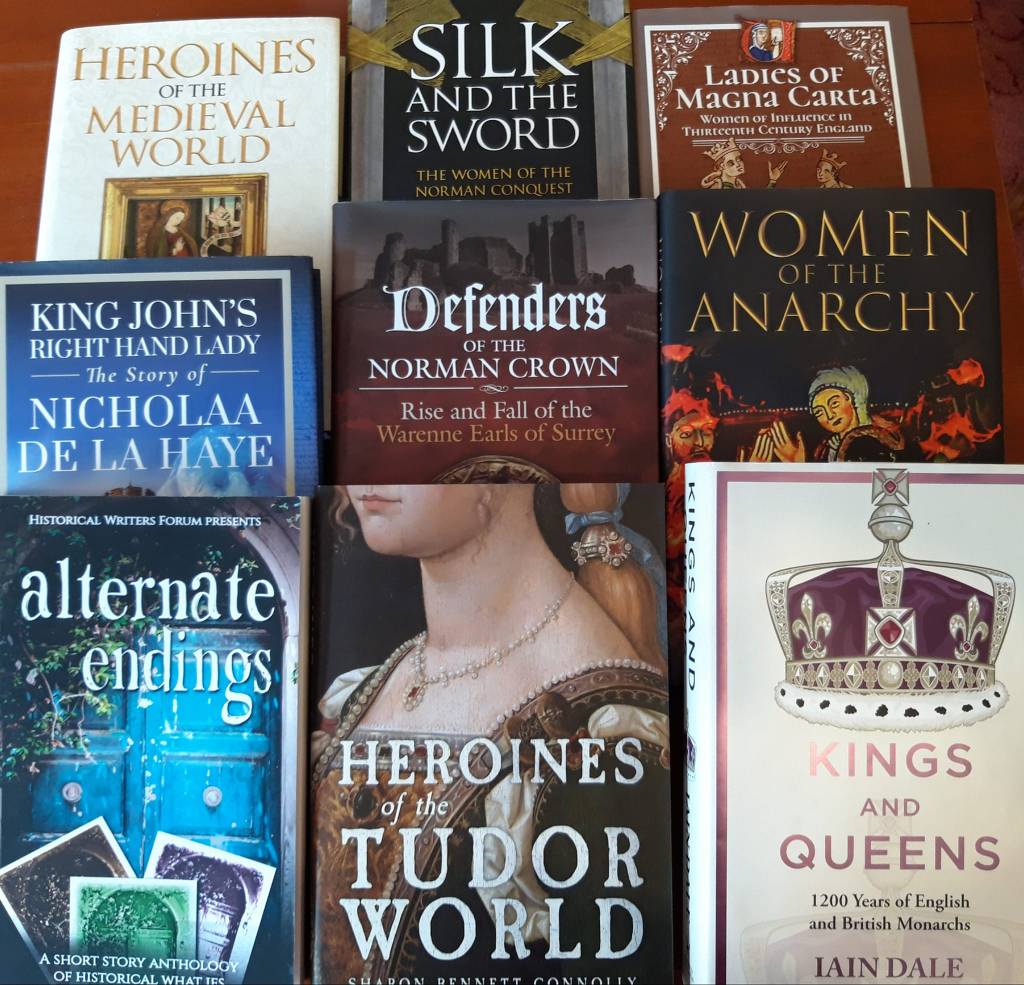

OUT NOW! Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. There are now over 40 episodes to listen to!

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS