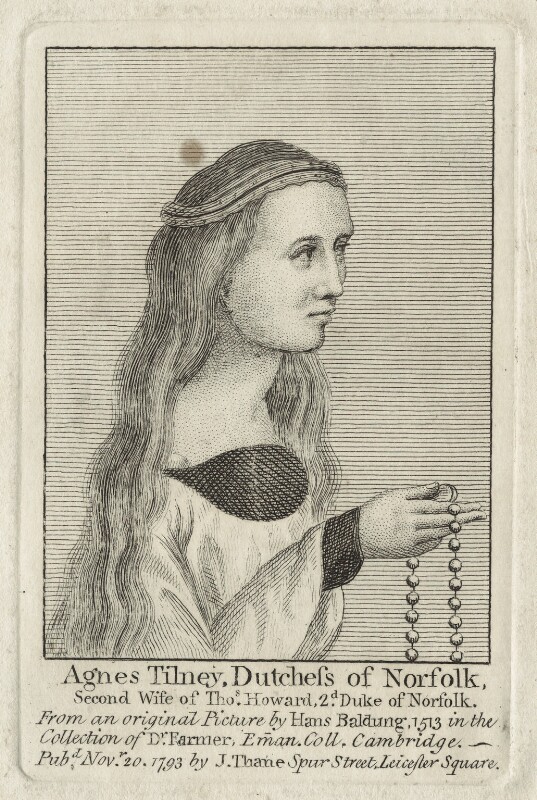

In Tudor times – well, in every era to be honest – not every woman could boast a husband who was capable of greatness. Or even of managing his own finances. Anne de Vere, Countess of Oxford, was one such, a woman who survived the scandals attached to her family only to be faced with a profligate husband who really should have heeded his wife’s advice. Born Anne Howard, daughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk and his second wife, Agnes Tilney, she first appears in the historical record on 16 November 1511, when she is contracted to marry John de Vere, the 12-year-old nephew and heir of John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford. John was the only surviving son of George de Vere, who had been intended for the church until his father and oldest brother were both executed in 1462. He then became the heir of his surviving older brother, John de Vere, but died in 1503, leaving his 4-year-old son John as his brother’s heir.

The de Veres were an old, noble family and although the marriage was politically and economically advantageous to both sides, it was even more so to the Howards, whose relatively new nobility would be strengthened by links with the old families. Although the marriage took place in September 1512, the youth of Anne and John meant that the couple lived with Anne’s family, the Howards, and the marriage may not have been consummated for some time. A year later, John inherited his uncle’s earldom of Oxford but as he was a minor, he remained a royal ward, and in 1514 his wardship and lands were granted to his father-in-law, the duke of Norfolk.

Anne and John de Vere attended the famous Field of the Cloth of Gold in June 1520 and two months afterwards, the earl attained his majority and was granted livery of his lands. The young couple set up home at Hedingham Castle. The marriage does not appear to have been a happy one and by April 1523, Anne was writing to Cardinal Wolsey, requesting help in managing her husband’s behaviour. Though masked in diplomatic terms, Anne’s letters complained that John was managing his estates badly and acting dishonestly, and he refused to allow her to take on some of the estate management. Anne wrote that ‘yf I shuld medyl in anny off these concerns further than I do I surteyne that I shuld never leue in rest.’1

Anne had taken control of the household finances and asked Wolsey to intervene in the matter of her husband’s debt. She was also worried about the negative influence of her husband’s heir, his second cousin, Sir John de Vere – later the 15th earl of Oxford. With the help of her father, the duke of Norfolk, and half-brother, Thomas Howard, then Earl of Surrey, Anne petitioned Henry VIII and in February 1524 an ordinance was enrolled in the court of Chancery to limit John’s control over his household and finances and to improve his behaviour towards Anne. He was to make no grants or annuities without the advice of Cardinal Wolsey. A noble had a duty to manage his lands sensibly, both to preserve them for future generations and as evidence that he was fit for public life.

John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, was warned against keeping wild and riotous company and drinking to excess. He was to moderate his hunting and be caring and considerate of his wife. He was ordered to return to his father-in-law’s household until further notice, his lands placed in Wolsey’s nominal keeping. However, as early as 16 February, Wolsey wrote:

My lorde, the young countess of Oxford has lately returned to the King and Council, alleging that his lordship still keeps her out of possession, although it was supposed that she had entered by force of the King’s writ. A new commandment is sent out to the justices for removing the said force, and restoring her to her former possession. Informs him of it, that he may suffer her to have her … ‘ordinary course and way, whereby your title, possession, nor entry can not … to abide the same to be done by an extraordinary way … by reason whereof further trouble might ensue … to the hindrance of your matter and you.2

When Anne’s father died in May 1524, she and John probably moved to the household of her half-brother Thomas, now Duke of Norfolk. When the earl of Oxford’s health began to fail in July 1525, he was induced to sign a jointure by the Howards, which passed the bulk of his lands to his wife. He died the following year on 14 July 1526, at just26 years of age. At the time, Anne was living at Castle Camps in Cambridgeshire. She again wrote to Wolsey, advising him of difficulties with her husband’s executors and again asking for his help:

Since she wrote, the executors of the late earl of Oxford have, with much ado, delivered the stuff and plate bequeathed according to the letter directed to them by [Wolsey], but not the 100 marks. They declare they can do no more, and are displeased with Sir Rob. Drowre for being so ready to grant it to [Wolsey]. ‘They squared with him afore me, and now I find him better than the remnant in divers causes; and I desired them to have their advice in ordering my lord’s house, and in other great causes concerning my lord’s business, and they said they would not meddle,’ although they speak fair before [Wolsey]. Regrets to trouble him on this matter considering his great affairs, but has few powerful friends.3

The new earl of Oxford was not happy with the increase to Anne’s jointure, considering the lands that had been passed to her in 1525 to be rightfully his. By 11 August, she was again writing to Wolsey, complaining that the earl had twice broken into her deer park at Lavenham in Suffolk:

Received his letters on Saturday last, when she wrote to inform him of my lord of Oxford’s coming hither. He entered this town about 11 o’clock with 50 horsemen, and Sir John Raynsforthe came the same day with 30 horse. My lord broke open the park, his men entered with their bows ready bent, and killed 17 of her deer. On Tuesday he entered the park with about 500 men, having sent to the neighbouring towns to cause the people to assemble, and they killed 100 deer. The justice of the peace bound him and her to keep the peace, but he has to-day broken open her house at Campys, accompanied with 300 persons, beaten her servants and taken her goods. Asks his and the King’s aid. Lavenham, 11 Aug. Signed: A. Oxynfford.4

It was probably fortunate for Anne that she was absent from her home when the earl broke in, stole her goods and beat her servants. Had she been present, she may have been the subject of a kidnapping, or worse. Anne was not to give up in the face of such violence, however, and she set the wheels of the law in motion and appealed to her powerful relatives and friends for help. Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Henry Courtney, Earl of Devon, were amongst those who appealed to Cardinal Wolsey on Anne’s behalf. She informed Brandon:

The writ she had from Wolsey for Cambridgeshire does not serve her, for the persons at the castle of Campys answered the justices that they would not depart till their master ordered them. The justices did not think they could remove them by their own power, or by raising the country, without greatly disturbing the King’s peace. They have proceeded no further in executing the said writ. Sheannot obtain her possessions without his help and her brother’s (Norfolk). Wyttysforthe, 22 Aug.5

In 1528, the king settled Lavenham on Anne, but the earl immediately invaded the park, stole deer and beat the keeper. Anne joined forces with other de Vere relatives, who stood to be disadvantaged by the earl’s claims. The case was brought to arbitration before peers in 1529 when Anne’s jointure was reduced and most of the disputed lands were granted to the earl. The final remnants of the dispute were settled by March 1532. Anne lived quietly in Cambridgeshire afterwards, occasionally visiting London and the court. She was at the coronation of her half niece Anne Boleyn in 1533 and was one of the mourners at Catherine of Aragon’s funeral in 1536 and at that of Jane Seymour in 1537. In 1541, on the arrest of her mother and her sister Katherine, Countess of Bridgewater, for misprision of treason following the discovery of the adulteries of her niece Katherine Howard, Anne was given custody of her niece Agnes ap Rhys, daughter of her sister Katherine.

Described as a woman of great wit, Anne was faced with a number of lawsuits later in life from servants and tenants. One servant complained that she had taken against him after fourteen years of service, not only dismissing him from her service but also ‘expelling him unlawfully from the land and tenement he was leasing from her, stolen livestock from him, put a new lock on his cottage, and taken a number of loads of hay, and all of the rye that was growing.’6 Unfortunately, we do not have the outcomes of any of the cases brought against Anne, but they do perhaps demonstrate that she was having difficulty managing her estates later in life.

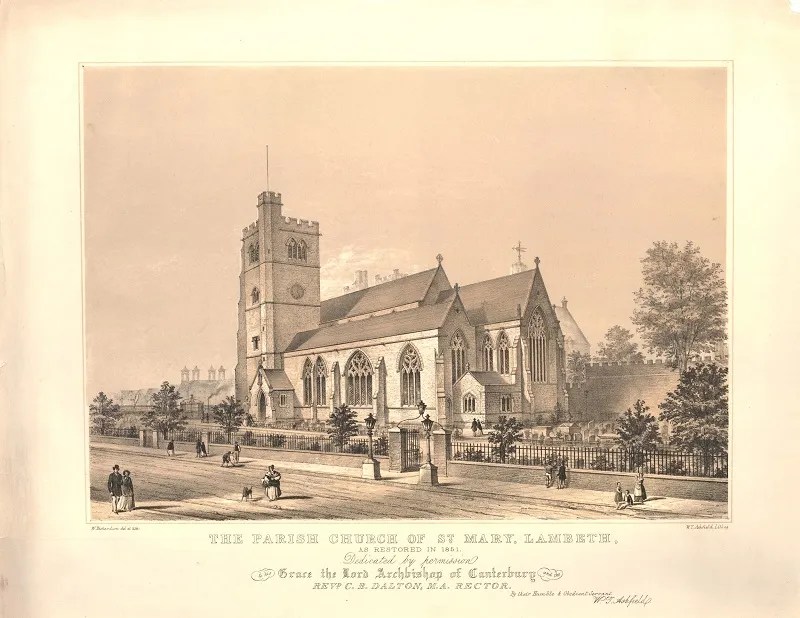

Anne died in early 1559, and although we do not have a will, the diarist Henry Machyn recorded the transport of her hearse to Lambeth and her funeral at the Church of St Mary’s in Lambeth, where she was buried in the Howard family chapel.

The xvij day of Feybruary was a herse of wax [erected] gorgyously, with armes, a ix dosen penselles and armes, [for the] old lade contes of Oxford, the syster to the old Thomas [duke of] Norffoke, at Lambeth…

The xxj day of Feybruary my lade was browth in-to Lambethe chyrche for the qwer and dobull reylyd, and hangyd with blake and armes; and she had iiij goodly whyt branchys and ij dosen of grett stayffes torchys, and ij haroldes of armes, master Garter and master Clarenshus, in ther cotte armurs; a-for a grett baner of armes, and iiij baners rolles, and iiij baners of santtes; and then cam the corsse, and after morners; the chyff morner was my lade chamberlen Haward, and dyvers odur of men (and) women; and after durge done to the dukes plasse; and the morow, masse of requiem done, my lade was bered a-for the he awtter.22

Anne de Vere, Countess of Oxford, had proved herself capable of defending her rights and property by using her wit and connections in order to solicit the support she needed to combat her husband’s profligacy. That she did not win out entirely against her husband’s successor is perhaps more a demonstration of the establishment’s desire to preserve earldoms with all their land, rather than of any failing on Anne’s part. Anne did prove that estate management was not the preserve of men!

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Notes:

1. TNA SP1/27, fols. 154v–155 quoted in Nicola Clark, ‘Vere [née Howard] Anne de, countess of Oxford’; 2. ‘Henry VIII: February 1524, 16-28’, in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 4, 1524-1530, ed. J S Brewer (London, 1875), pp. 41-58. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol4/pp41-58 [accessed 6 April 2023]; 3. ibid; 4. ibid; 5. ibid; 6. Nicola Clark, ‘Vere [née Howard] Anne de, countess of Oxford’; 7. ‘Diary: 1559 (Jan-Jun)’, in The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, 1550-1563, ed. J G Nichols (London, 1848), pp. 184-201.

British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/camden-record-soc/vol42/pp184-201 [accessed 6 April 2023].

Select Bibliography:

Nicola Clark, ‘Vere [née Howard] Anne de, countess of Oxford’; Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 4, 1524-1530, ed. J S Brewer; The Diary of Henry Machyn, Citizen and Merchant-Taylor of London, 1550-1563, ed. J G Nichols; Amy, The Sixteenth Century in 100 Women; David Loades, editor, Chronicles of the Tudor Kings: The Tudor Dynasty from 1485 to 1553: Henry VII, Henry VIII and Edward VI in the Words of their Contemporaries; Elizabeth Norton, The Lives of Tudor Women; Victoria Sylvia Evans, Ladies-in-Waiting: Women who Served at the Tudor Court; Claiden-Yardley, Kirsten, The Man Behind the Tudors: Thomas Howard 2nd Duke of Norfolk; Gareth Russell, Young & Damned & Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the Court of Henry VIII; Josephine Wilkinson, Katherine Howard: The Tragic Story of Henry VIII’s Fifth Queen

*

My Books:

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Coming 30 January 2025: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

Available for pre-order now.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell, and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Our latest episode is a fascinating discussion with Dr Ian Mortimer about the speed of travel and communications in medieval times. Definitely worth a listen!

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS