As many of my readers will know, one of my favourite all-time writers is the brilliant Alexandre Dumas, the author of The Three Musketeers. Dumas also wrote of Marguerite de Valois, La Reine Margot, who appears in my latest book, Heroines of the Tudor World.

Marguerite was the youngest surviving daughter of King Henri II of France and his queen, Catherine de Medici. She was born at the Château of St Germaine-en-Laye on 14 May 1553. She was her parents’ seventh child; their third daughter. She was raised alongside her two older sisters, Elisabeth (born in 1545) and Claude (born in 1547). Her brothers closest in age to her were Charles (born in 1550), Henri (born in 1551) and her younger brother Hercules (born in 1555), who would change his name to François when he was confirmed. Her brother, Henri, only two years older than her, was Marguerite’s closest family friendship as a child, though this did not last into adulthood. Henri would eventually rule France as King Henri III, succeeding to the throne on the death of his older brother Charles IX. Marguerite’s oldest brother was Francis – the future Francis II – who was born in 1544 and would go on to marry Mary, Queen of Scots. Another brother, Louis, died in 1550 at the age of just eighteen months.

Marguerite experienced tragedy at an early age, when her father, Henri II, died in July 1559, ten days after a jousting accident in which a lance had pierced his eye. Marguerite was only six years old. The princess was well educated and studied literature, classics, history, and a number of ancient and contemporary languages. She was also taught the complexities and dangers of sixteenth century politics and saw her mother acting as regent for her brother, Charles IX, becoming the most powerful person in France and a woman of international importance.

As a teenager, Marguerite fell in love with Henry of Guise. He was a duke from a prominent family, but when they were found out, Henry was exiled from court and Marguerite was beaten so badly by her mother and brother, Charles IX, that her clothes were torn and ruined. The Guises might be a powerful family, and the most powerful Catholic faction at court, but their influence and popularity were a threat to the government of Catherine de Medici and the queen was not about to increase their prestige further by allowing the duke to marry her daughter.

Marguerite was a princess of France and not free to follow her heart.

The family had other plans for her marriage. Queen Catherine arranged with Jeanne d’Albret, Queen of Navarre, that Marguerite would marry her son, the Huguenot prince, Henri of Navarre. Although he had grown up at the French court, Henri’s mother had insisted that he be raised a Protestant. Henri was from the Bourbon branch of the French royal family and was the closest male relative to the throne after Marguerite’s brothers, he was the ‘First Prince of the Blood.’ Should her brothers die without producing heirs of their own, Henri of Navarre, though a Protestant, would be next in line to the throne. In 1572, when Marguerite and Henri married, Henri’s succession would have been only a distant possibility, with the twenty-two-year-old king, Charles IX, recently married himself and hoping for an heir; and two younger brothers to follow him should he not provide a son of his own.

The marriage of Henri and Marguerite was intended to rebuild family ties and broker peace between the French Catholics and the Huguenots, the French Protestants. Since 1560, France had been riven by factions, with the powerful Guise family championing the prospect of eradicating Protestantism within France, backed by Spain and the papacy. The Bourbons, led by Henri of Navarre’s mother, Jeanne d’Albret, led the Huguenots, French Calvinists. As queen, Catherine de Medici tried for compromise, wanting France to be independent of foreign powers, such as Spain and the papacy. Tens of thousands of French had died in the religious wars, despite the signing of a number a peace treaties, which never held. The 1572 Peace of St Germain-en-Laye was to seal the treaty with a wedding.

Of Marguerite, her future daughter-in-law, Jeanne d’Albret wrote:

‘As for her beauty, I agree she has a good figure but she holds herself in too much. As for her face, she uses so much help, it does irritate me, because she will ruin herself. But in this court make-up is normal just like in Spain.’1

Marguerite was a pawn in the midst of this political dispute. Born in December 1553, Henri was seven months younger than his bride. He and Marguerite were second cousins, both being the great-grandchildren of Charles, Count of Angoulême and his wife, Louise de Savoie. Marguerite descended from their son, Francis I, King of France, while Henri was descended from Francis’s sister, Marguerite d’Angoulême, Queen of Navarre. The young couple was betrothed in April 1572 and appeared to like each other at first, though it soon became evident that there was no chemistry between them, no physical attraction. It would be the first royal marriage between a Catholic and a Protestant. Henri’s mother, Jeanne d’Albret died before the wedding could take place, in June 1572, making Henri the new king of Navarre.

The wedding ceremony took place at the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris, atop a platform that had been erected on the western façade of the church and hung with cloth of gold, so that everyone could watch; Protestant Henri refused to be married within the Catholic cathedral and so the wedding would be conducted outside. At three o’clock in the afternoon, the king of Navarre and his entourage made a stately procession to the church. Henri was dressed in a doublet and cape of rich yellow satin, embroidered with diamonds and pearls. He was escorted by two of the bride’s brothers, the dukes of Anjou and Alençon.

The vast crowds were there to see Marguerite, described as ‘the greatest beauty in the world’ by a Neapolitan ambassador. She was led from the archbishop’s palace, close to the cathedral, by her brother, King Charles IX. The princess was wearing an ermine-trimmed gown of royal blue silk. Her fifteen-foot train was carried by three ladies-in-waiting. The ceremony was officiated by the Cardinal de Bourbon and when he asked Marguerite if she would take Henri as her husband, she refused to answer; her brother pushed her head so that she appeared to nod, and the cardinal took this to be her assent. The vows concluded, Marguerite and her party went inside the church to hear Mass, while Henri and his entourage waited outside.

There were three days of feasting to celebrate the marriage of Henri and Marguerite, the King and Queen of Navarre, before the peace was shattered by an assassination attempt on the Huguenot leader Gaspard de Coligny. Coligny was shot in the shoulder by the Sieur de Marevert. Firing from a house belonging to the duke de Guise, he had been aiming to kill. Coligny survived and was taken back to his lodgings, where the bullet was removed, the king sending his own physician to assist in Coligny’s treatment. Tensions were running high and Henri of Navarre and his attendants, staying at the Hôtel de Navarre, were nervous. On the morning of 24 August, Marguerite was woken by banging on her door, at which a blood-stained soldier staggered in, shouting ‘Navarre! Navarre!,’ pursued by two more men, armed with bows and arrows.

The St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre was proceeding through the streets of Paris. Maurevert’s attempted assassination of Coligny, probably at the orders of Henry of Guise, had caused the King and his mother to fear that they would be blamed. In order to prevent reprisals, they chose to strike first, sending their soldiers against the Huguenot leadership. Coligny was among those killed, his body thrown out of the window of his lodgings and burned by the crowd. As other Huguenots were cut down, the Catholic Parisians joined in the bloodbath, slaughtering their Huguenot neighbours. Marguerite and her husband both made it to safety at the Louvre Palace, where they were protected by royal troops. Henri’s friends and attendants were not so lucky and were butchered within earshot of the newlyweds. As the violence spread to more cities in the following days and weeks, over 5,000 were killed.

The leadership of the Huguenot faction had been dealt a serious blow. The older leaders were dead, murdered, and the younger leaders, Henri of Navarre and his cousin, Henri de Condé, were virtual prisoners, confined to the royal court and on 26 September 1572, Henri of Navarre renounced Protestantism. Four years later, he finally managed to flee the court, leaving his wife behind. Returning to the Protestant faith, he was now twenty-two and assumed the leadership of the Huguenots. Marguerite had remained at the French court following her husband’s flight. There’s was a rather liberal marriage, with neither one concerned if the other took lovers. Politically though, Marguerite worked in support of her husband, despite him being a Protestant and she being Catholic.

In 1578, Marguerite and her mother made a journey south, with Catherine de Medici hoping to build some bridges with the king of Navarre by delivering his wife to him. For the next five years, until 1583, Marguerite and Henri lived as husband and wife at Nérac, 100km south-east of Bordeaux. Initially, the marriage appeared to be experiencing a revival, but then Henri had an affair with on of Marguerite’s ladies, known as La Fosseuse, before moving onto a more serious relationship with Corisande de’Andouins, Countess of Guiche. In 1582 Henri III, King of France, summoned Marguerite back to court, with the hope that her husband would follow. Marguerite came but Henri did not.

While back at the French court, Marguerite had an affair with Jacques de Harlay, Sieur de Champvallon, and there were rumours that she was pregnant by him. Marguerite was ordered to leave court by her brother and left Paris on 8 August. As she travelled south, her party was stopped by a troop of royal archers, who insulted Marguerite and arrested two of her ladies. They were questioned about Marguerite’s baby, if there was one. All trace of the child, whether she was pregnant or not, had disappeared. On 13 April, Marguerite was reunited with her husband at Port St Marie, just north of Nérac. Just two months later, they heard of the death of Marguerite’s youngest brother, Francis, Duke of Anjou, who was a close ally of Henri of Navarre.

Francis’s death was a pivotal moment for the king of Navarre. He had been the heir of his brother Henri III and now, the heir was Henri of Navarre himself, at least until Henri III were to have a son of his own. The Holy Catholic League, however, funded by the king of Spain and the papacy, recognised the ageing and childless Cardinal de Bourbon as the heir to the throne. On 31 March 1585, the cardinal issued a proclamation promising to restore France to Catholicism and declaring that ‘subjects are not required to recognise or sustain the domination of a prince who has parted from the Catholic faith…’ On 9 September 1585 Pope Sixtus V excommunicated both Henri of Navarre and his cousin Condé – even though they were Protestants – and deprived them of their hereditary rights. He even declared that Henri had no right to the kingdom of Navarre. Henry of Guise was manoeuvring to promote his own candidacy for the throne of France by excluding Henri of Navarre.

After the death of his brother Francis, Henri III was forced to make war on Navarre by Henry of Guise, thus starting the War of the Three Henries. It was at this point that Marguerite took her life and future into her own hands. Having realised that she could not be content living with Henri, she left his court and moved to Agen, claiming she wanted to devote herself to the celebration of Easter. She joined the Holy Catholic League and with 2,000 soldiers she took Agen and held it in the name of the League. But after a bout of plague was seen as the punishment of God for Marguerite rebelling against her husband and brother, and the destruction of the garrison gunpowder left the city indefensible, she was forced to abandon Agen and moved further inland to another of her fortresses at Carlat.

As she left for Carlat, Marguerite was arrested by her brother’s forces under the command of the Marquis de Canillac, who escorted her to the great fortress at Usson. Marguerite charmed Canillac and within a year she was no longer a prisoner, but the sovereign lady of the territory, in the heart of the Auvergne. Marguerite spent the next 19 years living in Usson, as the Wars of Religion ground to their conclusion with a succession of deaths. The duke of Guise died in 1588, killed on the king’s orders. Catherine de Medici died in January 1589, just a few months before her 70th birthday. And in August 1589, King Henri III was assassinated by a Catholic enthusiast.

This left Henri of Navarre as the victor, though the war continued for 4 more years, as the Catholic League refused to accept a Protestant king. In 1593 Henri’s conversion to Catholicism, supposedly with the words ‘Paris is worth a Mass,’ Henri of Navarre became King Henri IV of France, his coronation taking place in Chartres Cathedral in February 1594. The Edict of Nantes finally ended the Wars of Religion in 1598, establishing Catholicism as the state religion in France, but allowing Huguenots to worship freely in many parts of France (excluding Paris). Though she was no longer living with Henri, Marguerite, the last surviving child of Henri II and Catherine de Medici, was now Queen of France and Navarre, and she and Henri were back on good terms. She established her court at Usson, writing her memoirs and poetry and building a library.

In 1593 Marguerite made an agreement with Henri whereby he would give her 50,000 francs a year and pay her debts of 200,000 écus in return for her applying for the annulment of their marriage; she cited her barrenness, consanguinity and that she was forced to marry against her will as grounds for the annulment. Though the annulment was not granted by the pope until 1599, it did eventually leave Henri free to marry again, to Marie de Medici, and produce the all-important heir – the future King Louis XIII. Although she had been a pawn to the political manoeuvrings of her mother on her marriage to Henri of Navarre, Marguerite had, to all intents and purposes, managed to forge her own path in her later years. Her agreement to the annulment of her marriage meant the continuation of the line of Henri IV and secured the future of France. Marguerite returned to Paris in 1605 and lived there until her death in 1615.

Footnotes:

1. Dominic Pierce, ‘The Unique Career of Marguerite de Valois, Queen of Navarre’, tudortimes.co.uk

Images:

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Sources:

Dominic Pierce, ‘The Unique Career of Marguerite de Valois, Queen of Navarre’, tudortimes.co.uk; Nancy Goldstone, The Rival Queens: Catherine de Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois and the Betrayal that Ignited a Kingdom; Frieda Leonie, Catherine de Medici: A Biography; Pierre Groubert, The Course of French History; Estelle Paranque, Blood, Fire & Gold: The Story of Elizabeth I and Catherine de Medici; Amanda Prahl, ‘Biography of Margaret of Valois, France’s Slandered Queen’, thoughtco.com; François Bayrou, Henri IV: Le Roi Libre; Alexandre Dumas, La Reine Margot.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Coming on 15 June 2024: Heroines of the Tudor World

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. These are the women who made a difference, who influenced countries, kings and the Reformation. In the era dominated by the Renaissance and Reformation, Heroines of the Tudor World examines the threats and challenges faced by the women of the era, and how they overcame them. From writers to regents, from nuns to queens, Heroines of the Tudor World shines the spotlight on the women helped to shape Early Modern Europe.

Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Out Now! Women of the Anarchy

Two cousins. On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

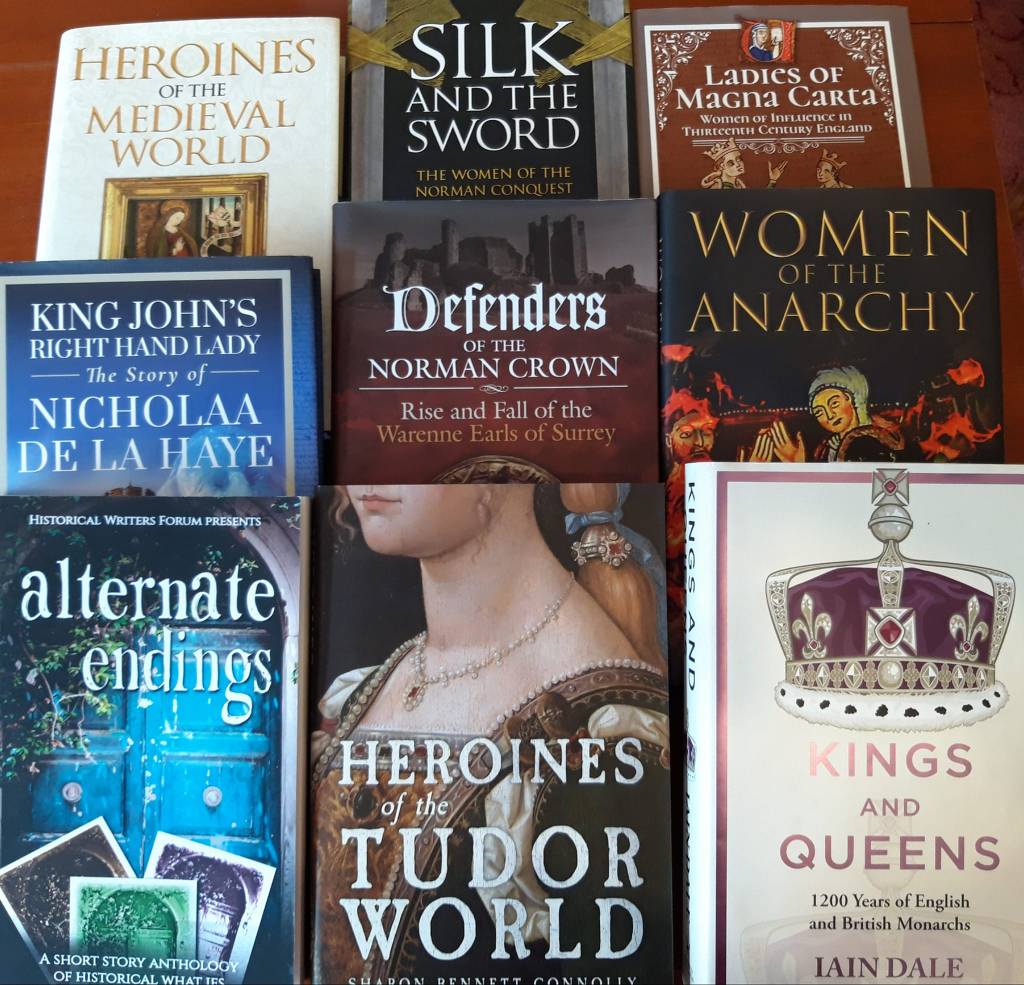

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops or direct from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon. Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

*

©2024 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS.