Today, it is a pleasure to welcome historian John Marshall to History…the Interesting Bits to chat about his writing and what attracts him to History. John’s third book, Othon de Grandson: Edward I’s Loyal Knight of Renown, has just hit the shops. A close rival to William Marshal for the Greatest Knight accolade, I’m looking forward to reading Othon’s story. But first, a chat with John about what inspires his writing…

Sharon: How did you start your writing career?

John: A midlife career change, some would say a midlife crisis, but an increasing dissatisfaction and boredom surrounding my career of thirty years within the corporate travel business. In short it was not fun anymore, nor was it in anyway stimulating intellectually. I had had a lifelong interest in history, so the first step was a master’s in history. More than anything, this taught me how to organise my thoughts and conduct research professionally, especially that in reading the most interesting stuff was usually in the footnotes. A relocation for personal reasons brought a move from England to Switzerland. There, I kind of fell down the rabbit hole of the relations between Savoy and England in the thirteenth century, I was looking for a writing project as a historian and within a week of arriving in Switzerland my partner and I visited the castle at Yverdon in the Canton of Vaud. Hidden away in the small print of a panel was the throw away line that the castle had been built by Maître Jacques de Saint George. I had recently visited Conwy castle before leaving the UK and for some reason the name immediately registered as the man who had built Conwy. “Do you know who this is?” I asked my partner, receiving a puzzled look. I then emailed the castle to be given an erroneous answer. I then discovered the works of the late Arnold Taylor, and the more recent criticism which I thought unfair. So, the research for my first book, Welsh Castle Builders began.

Sharon: What is the best thing about being a writer?

John: We all write to understand something better, we all read for the same reason. We also, as was the case with me, write a book we would have wanted to read ourselves. In beginning the research for Welsh Castle Builders I was frustrated that the available evidence, the story, did not seem to be in one place. I also felt that the people I wanted to write about in the distant past had not had their story told well enough. So, the best thing about being a writer is being able to write books you would want to read yourself and to tell the stories of forgotten people.

Sharon: What is the worst thing about being a writer?

John: For a history writer the worst thing is the sheer volume of detail, and the ease with which you can make mistakes by saying castle x is in county y when it’s now in county z. My previous career had involved a whole lot of data analysis, so this helped, but the sheer volume of detail can be daunting. I would also add that the hours involved in research can also be daunting.

Sharon: What got you into history?

John: My dad was the one who got me into history, it was very much a father and son thing. He had a real passion for history; we covered many miles visiting castles and battlefields. Indeed, my earliest childhood memory is a vague one of walking by an enormous castle by a river and wondering who built that. As a five-year-old boy a medieval castle had a “wow” response that never left me. We were on holiday in Rhyl, I now know the castle has a name, Rhuddlan Castle.

Sharon: What drew you to Othon de Grandson’s story?

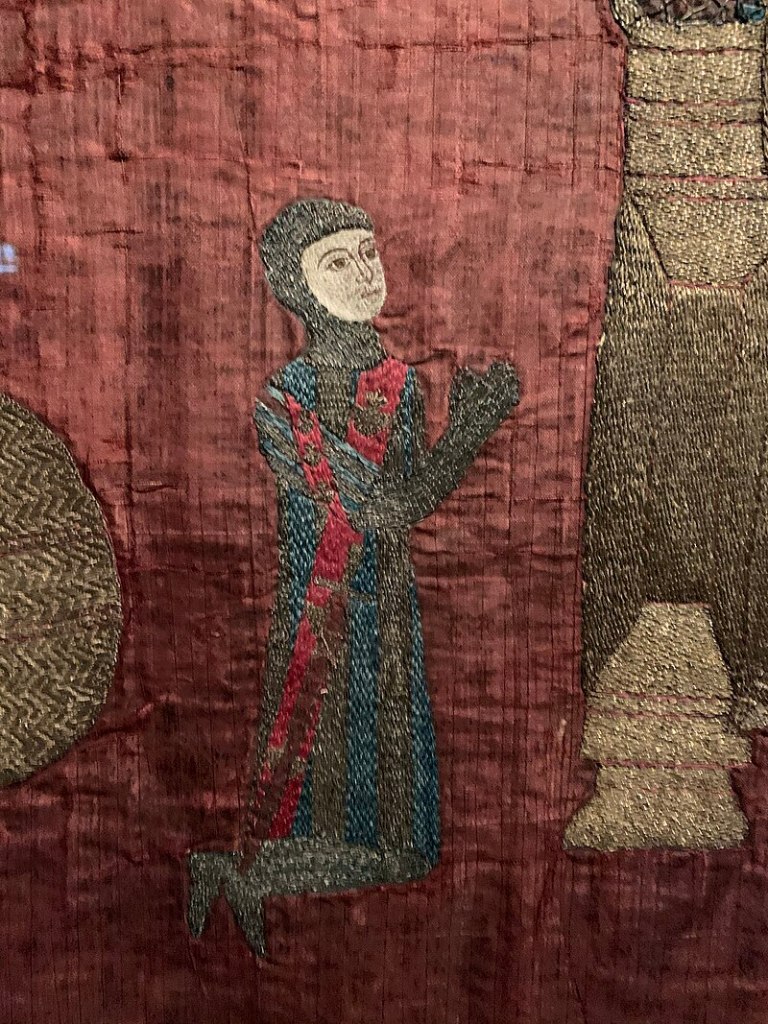

John: Days after visiting the castle at Yverdon my partner and I visited the cathedral at Lausanne. My partner is from Lausanne, and she was and is very proud of the cathedral. Just by the altar is the tomb of a knight, with no reference to who the knight is. Asking my partner she replied, “Oh that’s Othon de Grandson” But she was not able to add much more. Reading Arnold Taylor, in connection to the Yverdon visit the name Othon de Grandson kept coming up time and time again. So, I began to learn Othon’s story and realised quickly that without Othon there would have been no Maître Jacques de Saint George in Britain. More research told the story of a boy who came to England, a crusading knight, a top-level diplomat, someone at the very heart of European affairs. Perhaps it was the little boy in me, but this had all the hallmarks of a Boy’s Own adventure story. So, once I had done with Maître Jacques and Pierre de Savoie, Othon’s story had to be told. There was an excellent book written in the sixties, but this story needed to be told again, maybe one day the Swiss will even put a marker on the tomb to say who it is.

Sharon: How influential was Othon to Edward I’s reign?

John: I think it comes down to one word – loyalty. The book is called Othon de Grandson: Edward I’s Loyal Knight of Renown. Edward I could inspire incredible lifelong loyalty in those around him. It is remarkable to see how loyal these band of brothers; Edward, Edmund, Othon de Grandson, Henry de Lacy, Jean de Vesci et al were to one another. The epithet that seems to come up time after time in their regard is loyalty. Edward in March 1278 described Othon as someone who could ‘do his will … better and more advantageously’ than ‘others about him’, as well as ‘if he himself were to attend to the matters in person’. Delegation, even in our own day is an art, and Edward chose wisely those around him. Being a monarch in the Middle Ages was no easy task, and having people you could trust to do something exactly as you would do it yourself was like gold dust. Loyalty was foundational to medieval ideas of knighthood. It was not just important it was central to their identity, purpose, and honour. What stands out about these band of brothers is that their bonds were formed through shared hardships: crusades, rebellion, foreign war, and dynastic tension. Loyalty was more than service—it was a mark of faith, honour, brotherhood, and identity. French historian Charles-Victor Langlois wrote of Edward:

“We cannot admire the activity of the English king too much; he was both in the breach on the side of the Rhône valley and of Wales; the threads of all European intrigues, in Castile, in Aragon, in Italy, were connected in his hands; and he still found the leisure to watch over his interests on the continent as Duke of Aquitaine.”

How could Edward do this? He had an Othon.

Sharon: How do you conduct your research?

John: The answer is reading, reading, and reading. But more than that paying especial attention to primary sources and more that that especial attention to sources in other countries. The subjects of these histories, especially Othon de Grandson, lived their lives across the whole of the European theatre, and so their story is to be found everywhere. But I would sound a note of caution, to be careful in handling medieval chroniclers, like writers today they usually politically span stories, omitted things they didn’t like, only including things they liked. We should use medieval chronicles very carefully. A good case in point is the conduct of Othon de Grandson’s conduct in the Fall of Acre in 1292. Some chroniclers praise him, others are very critical, some even accuse him of cowardice. But by giving greater weight to eyewitness accounts and especially those like the Templar of Tyre who seems to have been with the English knights at the end, we can arrive at the truest picture. Spoiler alert, he was not a coward.

I would also add that it is vital to get out from a book and walk in the steps of those you are writing about. To this end my partner and son have spent many hours under a hot sun in the deep undergrowth of the French countryside looking for castles that are today nothing more than a few stones on top of a steep hill. But it is crucial in understanding the people of the past to visualise the landscape in which they moved.

Sharon: What attracts you to the thirteenth century?

John: The thirteenth century is foundational in many ways to the world we know today. In Othon’s time we see the beginnings of the clashes between church and state. We also see knights like Othon who were of their day, the feudal system, that is loyalty to a suzerain not a nation state. Whereas we see at the French court of Philippe le Bel the likes of Nogaret who are outlining nascent ideas of nation as primary identity. It is the century where we begin to move from the Middle Ages to the modern. In Britain, the relationships between England, Scotland, and Wales are beginning to be set. Indeed, why Wales employs the English legal system and Scotland does not are founded in the thirteenth-century. We also saw in my previous book to this, Pierre de Savoie, the beginnings of our parliamentary system and sadly xenophobia too.

Sharon: The 13th century is just the best! But,are there any other eras you would like to write about?

John: I became a medieval historian on my arrival in Switzerland, but prior to that my university concentration and dissertation was the American colonial period. I might return to that at some point, but I may by typecast.

Sharon: What comes next? Are you working on a new book?

John: My fourth book, the story of Edmund, 1st Earl of Lancaster has just been written, the task of editing, especially on the part of my long-suffering partner, now begins. There has been a journal article written of Edmund, but it was written a century ago. During 2026 we plan to return from Switzerland to England, and in particular my hometown of Lancaster, so the subject of Edmund appeared like a bridge back to Lancaster – although he seems to almost never to have been there. The story of Edmund in many ways parallels that of Othon de Grandson. But Edmund’s story is one that fits into a brief period when it was not considered unusual for a Plantagenet prince to marry a Capetian queen and to rule French counties ((Champagne and Brie) that were so close to Paris. Edmund is the ancestor of our royalty today, both through his stepdaughter Jeanne I de Navarre but also in bloodline through his second son Henry. Edmund of Lancaster emerges as a very Anglo-French character, one that could only have existed in the rapprochement between the 1259 Treaty of Paris and the 1294 Gascon War. He is in many ways a model of a future that was not to be, where Plantagenets and Capetians happily coexisted, the road not traveled.

Sharon: Ooh, I like the idea of a book on Edmund. Good luck with that John and thank you so much for speaking with me today.

About the book:

There were once two little boys – they met when they were both quite young; one was born in what’s now Switzerland, by Lake de Neuchâtel, his name Othon de Grandson, and the other was born in London, his name Prince Edward, son of King Henry the third of that name. Othon was probably born in 1238, and Edward, we know, in June 1239. These two little boys grew up and had adventures together. They took the cross together, the ninth crusade in 1271 and 1272. Othon reputedly sucking poison from Edward when the latter was attacked by an assassin. In 1277 and 1278, they fought the First Welsh War against the House of Gwynedd, Othon doing much to negotiate the Treaty of Aberconwy in 1278, which ended hostilities. When war broke out again in 1282 they fought the Second Welsh War together. Othon led Edward’s army across the Bridge of Boats from Anglesey and was the first to sight the future sites of castles at Caernarfon and Harlech. Edward made his friend the first Justiciar (Viceroy) of North Wales. When Edward and Othon went to Gascony in 1287, Othon stayed in Zaragoza as a hostage for Edward’s good intentions between Gascony and Castille. Later, in 1291, when Acre was threatened by the Mamluks, Edward sent Othon as head of the English delegation of knights. When Acre finally fell to the Mamluks bringing the Crusades to a close, who was the last knight onto the boats? Othon de Grandson, helping his old friend, the wounded Jean de Grailly onto the boat. When Othon returned from the East, he found England at war with Scotland and France; he would spend his last years in Edward’s service building alliances and negotiating peace before retiring to his home in what is now Switzerland after the king’s death in 1307. Grandson lived in the time of Marco Polo, Giotto, Dante, Robert the Bruce, and the last Templars. He was right there at the centre of the action in two crusades: war with Wales, Scotland, and France, the Sicilian Vespers, and suppression of the Templars; he walked with a succession of kings and popes, a knight of great renown. This is his story.

Othon de Grandson: Edward I’s Loyal Knight of Renown is available now from Amazon.

About the Author:

Having moved to Switzerland, and qualified as a historian (Masters, Northumbria University, 2016), the author came across the story of the Savoyards in England and engaged in this important history research project. He founded the Association pour l’histoire médiévale Anglo Savoyards. Writer of Welsh Castle Builders: The Savoyard Style and Peter of Savoy: The Little Charlemagne both available from Pen and Sword Books Ltd. Member of the Henry III Roundtable with Darren Baker, Huw Ridgeway and Michael Ray.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

Out now: Scotland’s Medieval Queens

Scotland’s history is dramatic, violent and bloody. Being England’s northern neighbour has never been easy. Scotland’s queens have had to deal with war, murder, imprisonment, political rivalries and open betrayal. They have loved and lost, raised kings and queens, ruled and died for Scotland. From St Margaret, who became one of the patron saints of Scotland, to Elizabeth de Burgh and the dramatic story of the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the love story and tragedy of Joan Beaufort, to Margaret of Denmark and the dawn of the Renaissance, Scotland’s Medieval Queens have seen it all. This is the story of Scotland through their eyes.

‘Scotland’s Medieval Queens gives a thorough grounding in the history of the women who ruled Scotland at the side of its kings, often in the shadows, but just as interesting in their lives beyond the spotlight. It’s not a subject that has been widely covered, and Sharon is a pioneer in bringing that information into accessible history.’ Elizabeth Chadwick (New York Times bestselling author)

Available now from Amazon and Pen and Sword Books

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Heroines of the Tudor World tells the stories of the most remarkable women from European history in the time of the Tudor dynasty, 1485-1603. These are the women who ruled, the women who founded dynasties, the women who fought for religious freedom, their families and love. Heroines of the Tudor World is now available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how Empress Matilda and Matilda of Boulogne, unable to wield a sword themselves, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It shows how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other. Available from Bookshop.org, Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is the story of a truly remarkable lady, the hereditary constable of Lincoln Castle and the first woman in England to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Available from all good bookshops Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. Available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org. Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org. Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved. Our first ever episode was a discussion on The Anarchy Every episode is also now available on YouTube.

*

Don’t forget! Signed and dedicated copies of all my books are available through my online bookshop.

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter, Threads, Bluesky and Instagram.

*

©2025 Sharon Bennett Connolly, FRHistS and John Marshall