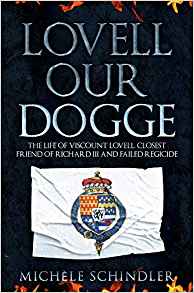

Today it is a pleasure to welcome Francis Lovell’s biographer Michele Schindler to the blog, with an article about Lovell’s wife, Anne FitzHugh Lovelle. Michele’s new book, Lovell Our Dogge, is out now. Over to Michele:

The discovery of Richard III`s remains in a car park in Leicester, seven years ago, has caused a surge of interest not only in the life of this controversial monarch, but also in his contemporaries. A particularly positive trend during these last years has been the interest showed in the women in Richard`s life, in the Wars of the Roses period in general. Whereas most of them have been typecast, if not outright ignored, over the last few centuries, many talented authors have focused on their lives, their influence, their politicial opinions, showing the fully rounded personalities they have been denied for so long.

Sadly, however, one influential woman has been strangely excempt from this trend. While her contemporaries have finally been allowed to emerge from the mists of history, Anne Lovell has not been given any attention. Ignored in history books, maligned in fiction, Anne`s importance in life has been all but forgotten.

Her life did not begin in a way that promised anything but rich and comfortable obscurity. Born as the third daughter and fourth child of Henry FitzHugh, 5th Baron FitzHugh, and his wife Alice Neville in 1460, Anne`s future probably seemed predictable, comprising of marriage to a member of the gentry or lower-ranking nobility and motherhood.

At least, this appears to have been what her parents were planning for her. In February 1465, when Anne was not more than barely five years old at the most, they married her to the then eight-year-old Francis Lovell, who had become Baron Lovell only around five weeks earlier after his father`s sudden death. It was a marriage made possible by Anne`s uncle Richard, Earl of Warwick, and would doubtlessly have been seen as a good match for the little girl.

It cannot be said how much Anne and Francis saw of each other in the first years of their marriage. It is known, however, that it was in the summer of 1466 that Anne`s mother-in-law, Joan Beaumont died, leaving Francis and his sisters Joan and Frideswide full orphans. After their mother`s death, it seems the girls were raised together with Anne and her siblings in her parents` household.

It is probable that during this time, Anne knew her sisters-in-law far better than her husband, who did not live in the same household she did. It was only some years later that he seems to have started living in her parents` household, but it is known that by 10th September 1470, he was definitely there, for he is included, together with Anne, her siblings and his sisters, in a pardon granted to Henry FitzHugh for his rebellion that year. It is one oft her very few early mentions of Anne in the sources, though it does not say anything about her personally. Only ten years old when the pardon was issued, her inclusion being a nominal one, not indicative of any of her actions.

The next mention of Anne found in contemporary sources is from 1473, by which time quite a lot in her life had changed. Now thirteen, she had lost her father the year before and seen her brother Richard become Baron FitzHugh. Though her father`s death meant that she and her siblings were the king`s wards, it seems that their mother Alice, had been allowed to keep custody of them, and in the summer of 1473, she and her children, Anne among them, joined the prestigious Corpus Christi Guild in York.

An interesting fact about this is that Anne`s husband, Francis, was present then as well and joined the guild with Anne and her family. This suggests Francis stayed with the FitzHughs regularly until Anne was old enough to be his wife in more than name, perhaps to give Anne the chance to get to know him, but there is no way to be certain. Nor do we know exactly when Anne was considered old enough, though some guesswork can be made. Francis made sure his sisters were not married before they were sixteen. It seems likely that he and Anne therefore also delayed cohabition and consummation until she had reached that age.

There evidence that this was also the age that Anne began living together with Francis, such as a letter written by Elizabeth Stonor in early March 1477. This letter refers to her and Francis, clearly as the Stonors` Oxfordshire neighbours. The context makes it clear that their relationship, while friendly, was still comparatively new and uncertain, which would fit perfectly with the Lovells, aged 20 and 16, first moving into Francis`s ancestral home of Minster Lovell Hall together around half a year before the letter was written.

The letter also contains an interesting minor mention of Anne, as the recipient of a present, like her husband, to win their good will. This indicates that the Stonors knew, or at least assumed, that Anne held some sway over her husband or meant something to him, as well as that she held some influence of her own, and that her friendship as well as his was worth cultivating.

Sadly, as so much of Anne`s life, evidence about her in the following years is scarce. She often visited her mother, usually together with her husband. Quite possibly, she also often saw her sisters, both of whom named their first daughter after Anne, and her brothers as well.

Even if she did not, she definitely saw her older brother Richard at court on 4th January 1483, as he acted as one of Anne`s husbands sponsors when he was created a viscount and Anne became a viscountess, and event that must have been splendid for her.

It was the beginning of a

steep career for her husband and following events would catapult Anne, too,

more into the limelight than she had been until that point. Only four months

later, King Edward IV died and six months later, Edward`s brother Richard had

become king, in a way that remains controversial to this day. Since the new

king was her husband`s closest friend, he was favoured a lot, which was to

reflect on Anne as well.

It is known that when Richard became king, Anne was present for

his coronation. She was in the new queen`s train, like her mother Alice and

older sister Elizabeth, and like them and several other ladies of high

standing, she was given “a long gown of blue velvet with crimson

satin” and “one gown of crimson velvet and white damask” for the

festivities.

Unlike her mother and Elizabeth, Anne was not made a

lady-in-waiting to Queen Anne, who was her first cousin, and unlike them, she

does not seem to have been favoured in any other way by the new queen. In fact,

it seems that after the coronation, she was not ever present in her household,

which means that her presence at the coronation had been an exception made for

the special occasion.

As to why Anne did not join her mother and sister in becoming a

favour lady of the queen, we can once more only speculate. It is possible, of

course, that the two women simply did not like each other. However, had Anne

wished to be a lady-in-waiting, it is almost impossible Queen Anne could have

denied her this, as she was the wife of one of the most important men in the

government. It is therefore most likely Anne herself decided that she was not

interested in the position, though the reasons for this must remain lost to

history.

Anne appears to have chosen to remain close to her husband whenever possible, which would mean she was at court often, and witnessed a lot of the events that remain so controversial to this day. Her opinions on them can never be known, but it seems that at the very least, she did not dislike Richard III.

Richard`s reign, famously, was not to last long, and within only two years of his accession, he was faced with an invasion, by an exiled Lancastrian earl named Henry Tudor. He employed Anne`s husband, among many others, to help him ward off this invasion. Perhaps with the danger of this task in mind, on 10th June 1485 Francis Lovell created an indenture in which he arranged for Anne to receive several manors in the event of his death, not just to keep for the rest of her life, but to own and be able to pass on to her descendants after her death. This was an unusual arrangement, and not at all one he would have needed to make, indicating that Anne was priced by her husband.

The fact that this arrangement would have enabled her to pass these manors on to her descandants also shows up an oddity. It is certain that Anne never had a child by Francis, yet even after what were likely nine years of living as man and wife, he does not seem to have at all blamed her for it, or, as can be seen from the indenture, even doubted she could have children. Since this arrangement could have disadvantaged any children Anne had by him, giving their half-siblings she potentially could have had by another man after Francis`s death a claim to these manors, it seems he thought or knew that their childlessness was his fault, though there is no telling why.

What Anne thought of this is, as always, up for speculation, but it does seem that she did not hold it against her husband. Nor does she seem to have held it against her husband that when Richard III was killed in battle, he chose not to accept the newly made Henry VII`s pardon. It is of course possible that she would have wished for him to do the same her brother Richard FitzHugh did, accept Henry VII, but once Francis`s decision decision was made, she supported it.

In march 1486, less than a year after Henry`s accession, Francis started a rebellion with two supporters, the brothers Humphrey and Thomas Stafford. It was a dangerous but not well thought-out undertaking, probably born more of desperation than any political thought, and not surprisingly, it failed. The brothers Stafford were captured and faced the consequences of their actions, but Francis was never caught, which seems to have been at least partly because Anne helped him. After the failure of the rebellion, the Countess of Oxford relayed information where Francis was hiding, which turned out to be inaccurate. Shortly afterwards, Anne`s brother Richard was stripped of several offices and the whole FitzHugh family, Anne included, watched with suspicion by the new government. Since Countess Margaret was Anne`s aunt and quite close to her mother, it is certainly far from impossible that the faulty intelligence where Francis was hiding came from Anne.

Anne remained under suspicion, and perfectly uncaring of the fact, for at least the next year. Famously, in 1487, with the support of Margaret of York, Dowager Duchess of Burgundy and John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, Francis started another rebellion in 1487, which would go down in history as the Lambert Simnel uprising. It was far better planned than the rebellion of 1486 had been, and once more, Anne appears to have been in contact with her husband and to have supported him.

In a letter to John Paston written on 16th May 1487, Sir Edmund Bedingfeld warned him that there were rumours he had met with “Lady Lovell”, and cautions him that he should act wisely about this rumour. Bedingfield does not spell out why he considers that such a meeting would be unthinkable, apparently certain Paston would know. Since only three months earlier, Paston had been chided by the Earl of Oxford, one of Henry`s closest men, for accidentally passing on wrong information regarding Francis`s whereabouts, it might very well be that Anne was suspected, or even known, to have once more deliberately spread bad intelligence. It can naturally not be proved today, but it certainly is remarkable that two people connected with Anne were provided with wrong information about Francis`s whereabouts at moments crucial for his escape.

It is obvious that the rebels, while in Ireland and Burgundy, must have had a contact in England, as they when they were landed on Piel Island in June 1487, they were already awaited by supporters. There is some evidence that this supporter in England was in fact Anne, and it seems that after Henry VII`s men had won the battle, she was surreptiously investigated. But whatever she did, it was apparently never proved, for Henry VII`s government enacted no punitive measures against her.

Interestingly, Anne does not seem to have been afraid of being punished, or else her concern for Francis overrode her fear, for in 1488, she was looking for her husband. We know this from another letter to John Paston, this one from Anne`s mother, in which Alice FitzHugh mentions that Anne was looking for Francis, supported by unnamed “benevolers“. For this purpose, she had send one of Francis`s men and fellow rebels, Edward Franke, to look for him, but he had been unsuccessful.

What is especially intriguing about this is that that Edward Franke was himself a traitor at that point, and knowing of his whereabouts without reporting them was treason in itself. It speaks volumes about Anne`s feelings for her husband that she did not care for the danger to herself when trying to find out what had happened to him. It is also an indication that she was courageous, and determined to find the truth.

The mention of the “benevolers”, whom she seems to have trusted and who seem to have supported her in this risky undertaking, appear to show that she was a well-liked woman who had several close, trusted friends.

We do not know if Anne ever found out what happened to her husband. It seems that sometime before December 1489, she gave up looking, as we do know that by then, she had taken a religious vow, for when Henry VII`s government granted her an annuity of 20 pounds then, she was called “our sister in God”. It means that at the age of 29 years at the most, Anne was certain she did not want to marry another time. Though of course her marriage prospects were diminished significantly due to her being a traitor`s widow, she could have found someone interested in her family connections, or even married for affection, but chose not to. Again, it can be taken as an indicator of feelings of affection for Francis.

We do not know what sort of vow she took, nor do we know what happened to her after that. The last mention of her in any source is in a second attainder passed against Francis in 1495, at which time she was spoken of as still alive. She might have died in 1498, but was definitely dead by January 1513.

Huge thanks to Michele for such a fabulous post!

About the author:

Michele Schindler is a language teacher, teaching German and English as second languages. Before that, she studied at Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, reading history with a focus on mediaeval studies, and English Studies. In addition to English and German, she speaks French, and read Latin.

Links to Michele Schindler’s book, Lovell Our Dogge: Amazon UK; Amazon US.

Links to Michele’s social media:

*

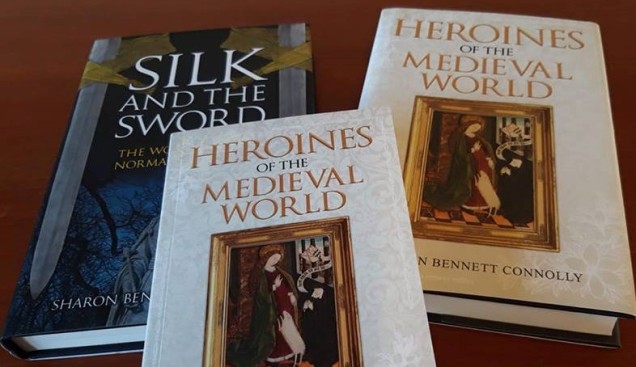

My Books

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest

From Emma of Normandy, wife of both King Cnut and Æthelred II to Saint Margaret, a descendant of Alfred the Great himself, Silk and the Sword: the Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon UK, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository and Amazon US.

Heroines of the Medieval World

Telling the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich, Heroines of the Medieval World, is available now on kindle and in paperback in the UK from from both Amberley Publishing and Amazon, in the US from Amazon and worldwide from Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2019 Sharon Bennett Connolly and Michele Schindler