Today it is a pleasure to welcome Author Susan Higginbotham to History … the Interesting Bits with a wonderful article about the correspondence between Mary Lincoln and Queen Victoria.

The First Lady and the Queen

Of the black-draped widows of the nineteenth century, surely two of the best known are Queen Victoria, who gave her name to the age, and Mary Lincoln, wife to the martyred American President. Bereaved just a few years apart, they would spend the rest of their lives in mourning.

Queen Victoria’s consort, Albert, died on December 14, 1861, at Windsor Palace. In due time, a formal letter of condolence arrived from the United States, signed by Abraham Lincoln, assuring the queen, “The American People . . . deplore his death and sympathize in Your Majesty’s irreparable bereavement with an unaffected sorrow. This condolence may not be altogether ineffectual, since we are sure it emanates from only virtuous motives and natural affection. I do not dwell upon it, however, because I know that the Divine hand that has wounded, is the only one that can heal.”

Mary Lincoln acknowledged the royal loss in her own way. On February 5, 1862, the Lincolns, at Mary’s suggestion, held a magnificent reception at the White House. The New York Herald reported the next day, “Mrs. Lincoln received the company with gracious courtesy. She was dressed in a magnificent white satin robe, with a black flounce half a yard wide, looped with black and white bows, a low corsage trimmed with black lace, and a bouquet of crepe myrtle on her bosom. Her head-dress was a wreath of black and white flowers, with a bunch of crepe myrtle on the right side. The only ornaments were a necklace, earrings, brooch and bracelets, of pearl. The dress was simple and elegant. The half mourning style was assumed in respect to Queen Victoria . . . whose representative was one of the most distinguished among the guests on this occasion.”

Not all of the press shared the Herald‘s enthusiasm. The country had settled into what would prove to be years of civil war, and the extravagant reception struck some as being in poor taste. The Pittsburgh Gazette of February 8, 1862, titling its short piece “Our Court Gone Into Mourning!” quoted the excerpt above, and then commented succinctly, “Don’t larf.”

Sadly, Mary would soon be wearing full mourning, and not as a courtesy for a distant queen. Her son Willie had fallen ill, and Mary had spent much of the reception going to and from his bedside. Though the prognosis initially appeared hopeful, Willie’s condition soon deteriorated, and he died on February 20, 1862. Mary could not bear to attend his funeral.

Unlike Queen Victoria, who put her entire court into mourning for Albert, Mary had only herself to attend to. (Unlike women, who when grieving for their closest relatives were expected to muffle themselves in deep, lusterless black if their means permitted it, men could get by simply with a black band around a sleeve or a hat–or with no mourning apparel at all.) Still, there was a fashion aspect to mourning, to which entire establishments catered, and Mary did not permit her terrible grief to prevent her from giving precise instructions to Ruth Harris, the hapless milliner who had the task of putting together a bonnet. “I want a very very fine black straw for myself–trimmed with folds of jet fine blk crape,” she instructed on May 17, 1862. Alas, the bonnet did not quite suit, so later that month, Mary explained, “I wished a much finer blk straw bonnet for mourning–without the gloss.”

By April 1865, however, Mary was wearing garments in an array of colors and looking forward to a brighter future. The war was all but won, and although President Lincoln had just begun his second term of office, he was looking forward to doing some traveling once he returned to private life. He hoped to visit Europe, as did Mary.

Abraham Lincoln, of course, never realized this dream, but was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865, and died the next morning.

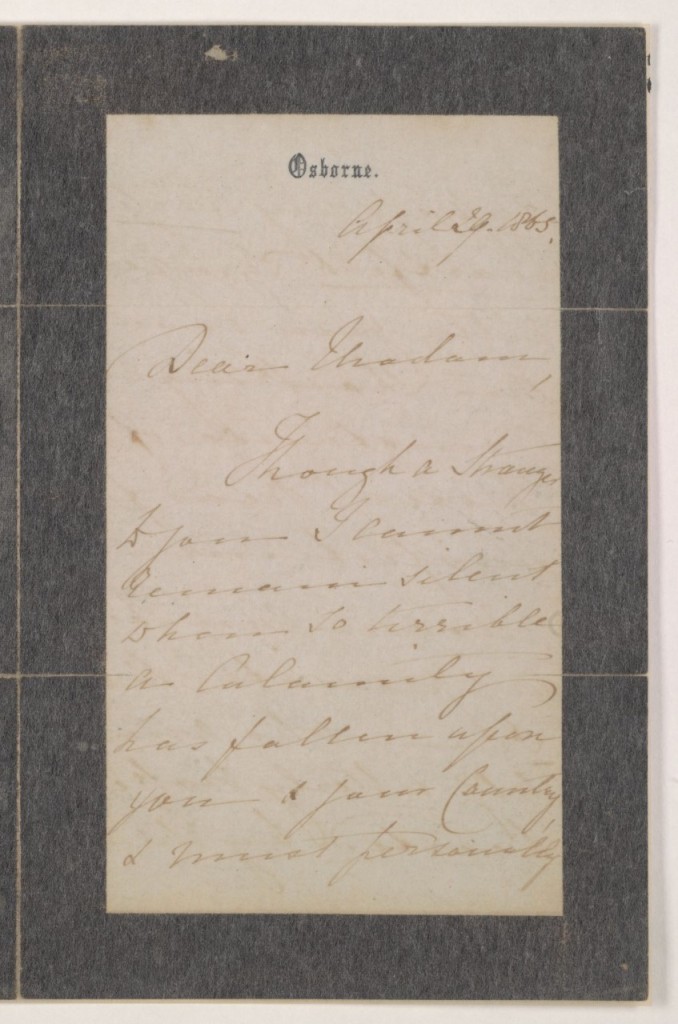

Several weeks later, Mary, who remained at the White House for over a month after her husband’s death, received the following black-bordered letter:

Osborne.

April 29, 1865.

Dear Madam,

Though a stranger to you I cannot remain silent when so terrible a calamity has fallen upon you & your country, & must personally express my deep & heartfelt sympathy with you under the shocking circumstances of your present dreadful misfortune.

No one can better appreciate than I can, who am myself utterly broken-hearted by the loss of my own beloved Husband, who was the Light of my Life, — my Stay — my All, — what your own sufferings must be; and I earnestly pray that you may be supported by Him to whom alone the sorely stricken can look for comfort, in this hour of heavy affliction.

With the renewed expression of true sympathy,

I remain,

dear Madam,

Your sincere friend

Victoria

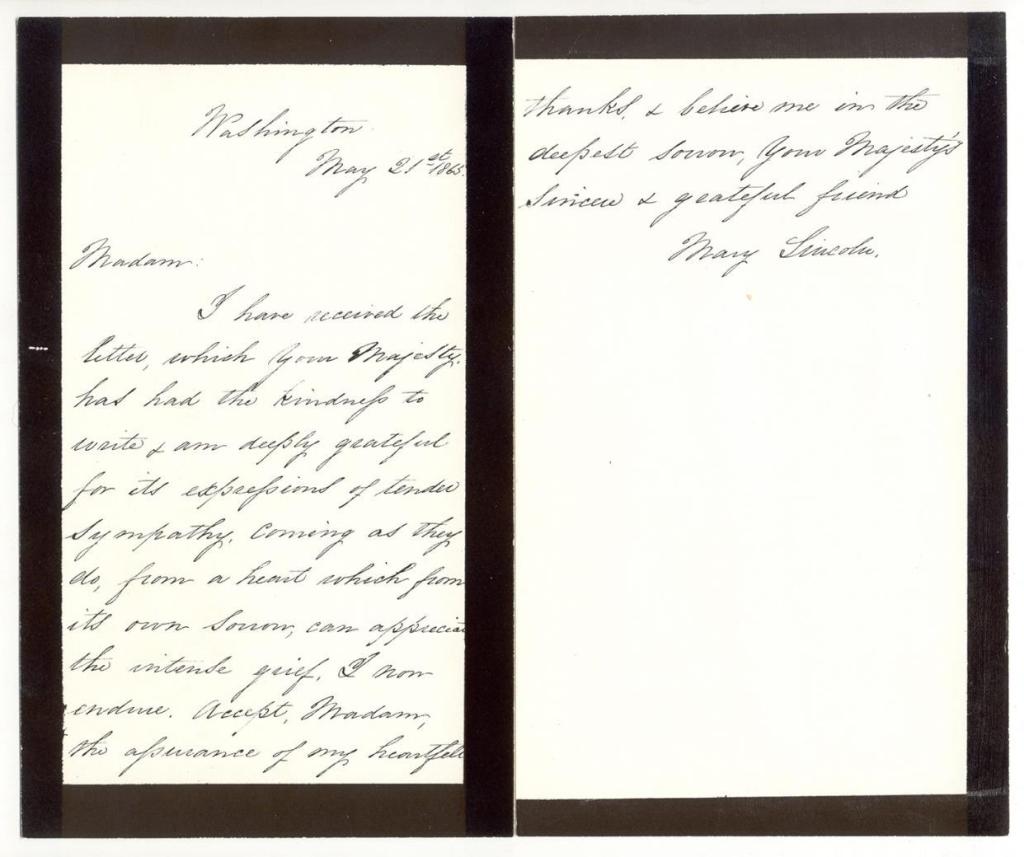

Mary responded with her own black-bordered letter:

Washington

May 21st, 1865

Madam:

I have received the letter, which Your Majesty has had the kindness to write, & am deeply grateful for its expressions of tender sympathy, coming as they do, from a heart which from its own sorrow, can appreciate the intense grief I now endure. Accept, Madam, the assurances of my heartfelt thanks &believe me in the deepest sorrow, Your Majesty’s sincere and grateful friend.

Mary Lincoln

On May 23, 1865, Mary Lincoln left the White House, and Washington, at last. Unable to stomach the idea of returning to Springfield, Illinois, where she had met her husband and spent most of her married life, she moved to Chicago, but found little comfort there. Finally, in October 1868, she and her youngest son, Thomas “Tad” Lincoln, sailed for Europe. Although she based herself in Frankfurt, she made an excursion to France. There, at Nice, Mary, traveling incognito, ran across Victoria and Albert’s eldest daughter, Victoria, Princess Royal, Crown Princess of Prussia. As Mary reported to Eliza Slataper on February 17, 1869, “She had alighted from her carriage and was selecting some gorgeous tablecovers–our eyes met & we looked earnestly at each other, yet until she left the store, I did not know, who she was. Of course she will always remain in ignorance, regarding me.”

That summer, Mary visited Scotland. “Beautiful glorious Scotland, has spoilt me for every other Country!” she reported to Eliza on August 21, 1869. Her Scottish tour included a stop at Balmoral Castle. Although Victoria was absent, Mary told her friend Rhoda White in a letter dated August 30, 1869, “I have every assurance, that as sisters in grief a warm welcome would be give me–wherever she is–yet I prefer quiet.”

Sadly, the sisters in grief were never to meet, although by the fall of 1870 Mary was staying in England, the climate of which disagreed with her and Tad, who was homesick as well. Mother and son returned to the United States in May 1871. Cornered by a “lady reporter” for the New York World, and asked to give her impression of the English people, Mary replied, as reported on May 16, 1871, “We were . . . very pleasantly received there, and enjoyed our stay exceedingly.”

As it turned out, Tad’s indisposition could not be cured by leaving behind London’s fog, and the youth died of a lung ailment in July 1871, just weeks after his return to America. His death launched Mary into a downward spiral, culminating in her son Robert’s decision to commit her to a private insane asylum in 1875. This at least invigorated Mary, who soon engineered her release. Declared “restored to reason,” Mary returned alone to Europe in 1876. but she seems to have avoided England, and even her beloved Scotland, entirely. In failing health, Mary returned to Springfield and died there on July 15, 1882.

Queen Victoria, however, had many more years to live, and seven years after Mary’s death would greet Abraham and Mary’s only surviving son, Robert, who was appointed minister to the Court of St. James in 1889. On May 25, Robert Lincoln presented his credentials to the queen at Windsor. The Chicago Tribune of May 26, 1889, reported, “Lincoln congratulated the Queen on her 70th birthday, and the Queen said some pleasant words to Mr. Lincoln about his father.”

Mary Lincoln would have been quite pleased.

*

It is always a pleasure to have Susan visit the blog, and I owe her a huge thanks for such an interesting article. I would like to take this opportunity to wish Susan every success with her latest novel, The First Lady and the Rebel. If you’ve never read one of Susan’s books, I highly recommend you take the plunge!

About the Author:

Susan Higginbotham is the author of seven historical novels, including Hanging Mary, The Stolen Crown, and The Queen of Last Hopes. The Traitor’s Wife, her first novel, was the winner of ForeWord Magazine’s 2005 Silver Award for historical fiction and was a Gold Medalist, Historical/Military Fiction, 2008 Independent Publisher Book wards. She writes her own historical fiction blog, History Refreshed. Susan has worked as an editor and an attorney, and lives in Maryland with her family.

From the celebrated author Susan Higginbotham comes the incredible story of Lincoln’s First Lady

A Union’s First Lady

As the Civil War cracks the country in two, Mary Lincoln stands beside her husband praying for a swift Northern victory. But as the body count rises, Mary can’t help but fear each bloody gain. Because her beloved sister Emily is across party lines, fighting for the South, and Mary is at risk of losing both her country and her family in the tides of a brutal war.

A Confederate Rebel’s Wife

Emily Todd Helm has married the love of her life. But when her husband’s southern ties pull them into a war neither want to join, she must make a choice. Abandon the family she has built in the South or fight against the sister she has always loved best.

With a country’s legacy at stake, how will two sisters shape history?

AMAZON | BARNES AND NOBLE | CHAPTERS | INDIEBOUND

*

My Books

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest

From Emma of Normandy, wife of both King Cnut and Æthelred II to Saint Margaret, a descendant of Alfred the Great himself, Silk and the Sword: the Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon UK, Amberley Publishing, Book Depository and Amazon US.

Heroines of the Medieval World

Telling the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich, Heroines of the Medieval World, is available now on kindle and in paperback in the UK from from both Amberley Publishing and Amazon, in the US from Amazon and worldwide from Book Depository.

*

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2019 Sharon Bennett Connolly and Susan Higginbotham