Guest post from David Santiuste

It is with great pleasure that I welcome historian David Santiuste to History … The Interesting Bits, with an article about Owain Glyn Dwr’s daughter, Catrin. Over to David.

Catrin ferch Owain Glyn Dŵr

I was very pleased to be invited to write something for History… The Interesting Bits – a blog I have followed for some time. Above all, I have appreciated Sharon’s efforts to raise awareness of some fascinating medieval women, whose stories are too often neglected. Another such woman is Catrin, a daughter of the Welsh hero Owain Glyn Dŵr, who ultimately paid a heavy price for her father’s ambitions.

Catrin was born after 1383, when Owain, then in his late twenties, married her mother, Margaret Hamner. Catrin was almost certainly one of his oldest legitimate children, although in time she would become part of a large family. Owain and Margaret had eleven children who survived infancy, in addition to Owain’s sons and daughters who were born outside marriage (probably when he was still a bachelor).

Catrin’s early years were presumably spent at her father’s house at Sycharth (near Oswestry). It was described by the bard Iolo Goch as a beautiful and lively place – ‘the fairest timber hall’ – where Owain offered lavish hospitality. Nevertheless, while he had evidently established himself as a man of some status, much of his early career was typical of the minor aristocracy. Through Owain, Catrin could claim descent from Welsh royalty, but her upbringing was surely intended to prepare her for an adult life within the same kind of setting – probably as the wife of a local gentleman who had connections with her family.

Naturally Catrin’s life changed in 1400, when her father launched a ferocious rebellion against King Henry IV of England. Sycharth was no longer safe – it was later destroyed by the English – although Catrin would soon find herself in much grander surroundings, as the rebels took control of many of Wales’s castles. Owain was acclaimed by his supporters as Prince of Wales, and for a time it must have seemed that Welsh independence had finally arrived.

In June 1402 Owain won a significant victory at the Battle of Bryn Glas, and the English commander, Edmund Mortimer, was taken prisoner. Edmund was treated with respect, and he became incensed when King Henry refused to pay his ransom – possibly because he was afraid of the Mortimers, whose strong claim to the throne had been passed over in his own favour. Edmund therefore decided to join Owain, who agreed to help him assert his nephew’s ‘right’ in England. The alliance was sealed in the time-honoured fashion, and Catrin became Edmund’s wife.

Catrin and Edmund had four children – a boy, Lionel, and three girls – although little else is known about their life together. However, their circumstances must have changed from 1405 onwards, as the English began to gain the upper hand in Wales. Owain avoided capture (his last recorded appearance was in 1412), but ultimately some of his family, including Catrin and Edmund, were pinned down at Harlech Castle. From this imposing fortress the Welsh continued to defy the English – and Edmund’s own exploits were celebrated by the bards – but the defenders were eventually starved into submission. The castle was surrendered in February 1409, by which point Edmund had already died.

After the fall of Harlech, Catrin and her surviving children were taken into custody, as was her mother, and they were later held in the Tower of London. They were all still there in June 1413, shortly after Henry V assumed the English throne, but Catrin passed away before the end of the year. The accounts of the Exchequer include a payment in December for her burial in St Swithin’s Church (which, intriguingly, is some distance from the Tower), together with her daughters.

Several historians, such as Terry Breverton, have suggested that Catrin and the others were put to death on the new king’s orders. This is partly based on the assumption that young Lionel was imprisoned with Catrin and subsequently disappeared; it is fair to say that Lionel, with his mixture of English and Welsh royal blood, might have posed a considerable threat to Henry if he had lived. Nevertheless, the evidence is ambiguous, as it is by no means clear that Lionel was taken at Harlech. It seems equally possible that he had already died, like his father – and that he was never in the Tower at all.

The fate of Catrin’s mother is also very uncertain, and one of Catrin’s daughters appears, in fact, to have outlived her; this is explicitly mentioned by the chronicler Adam of Usk, who was often well-informed. Besides, while Henry V could sometimes be a ruthless man, the notion that he ordered the murder of Catrin, and at least some of her children, does not sit well with the leniency he offered to other members of the Mortimer family (and even to Owain’s eldest son). Perhaps the conditions of Catrin’s imprisonment might have played a part, but it seems most likely that her death was due to natural causes.

Catrin was not entirely forgotten. She makes an interesting appearance, for example, in the first part of Shakespeare’s Henry IV. Edmund tells her fondly that ‘I understand thy kisses and thou mine’, but Catrin and her husband remain hampered by the language barrier between them. There is also tension between Catrin and her father, as they exchange words in Welsh, and one begins to suspect that Owain is not always a faithful translator. At last she tells her father that she will sing. Somewhat mollified, Owain instructs Edmund to rest his head in Catrin’s lap: so that she can ‘sing the song that pleaseth you, and on your eyelids crown the god of sleep.’

It is no longer clear what Shakespeare intended: the direction simply states that ‘here the lady sings a Welsh song’. Owain hopes, it would seem, that his daughter will provide a moment of calm before the storms ahead, and in many productions this is the effect achieved. She has been presented rather differently, however, in one recent American production. While her exhausted husband does rest his head in her lap, in this case Catrin’s song is no lullaby. Instead she offers a powerful lament, regretting man’s propensity for self-defeating war.

In keeping with her father’s reputed gifts as a soothsayer, there is also an element of prophecy in the song, as Catrin rightly fears for the future of her ‘home’ (which is surely meant in a broader sense here). The text is adapted from a poem by Hedd Wyn a Welshman who was killed during the First World War, yet even those who cannot understand the words can still appreciate the sense of urgency and pathos. Previously denied the chance to speak directly to the audience, Catrin eventually finds a way to make her message plain.

Another writer to give Catrin a voice is Menna Elfyn, who has imagined her experience of captivity in a moving series of poems. At first Catrin is imprisoned with her children, but then her ‘chicks’ are taken from her: ‘without a farewell kiss, without wrapping them warmly’. ‘They were born to a traitor’, spits out one man, brusquely, although their fate remains uncertain (both for the reader and for Catrin). She pleads with the guards – ‘Take me too. There’s a knife in my heart’ – but she is left in her cell to meet a lonely end.

The medieval church of St Swithin’s was destroyed in the seventeenth century, during the Great Fire of London, and with it Catrin’s tomb. However, she is now represented by a modern statue, which can be found in a garden on the site of the church. The sculpture is intended not only as a commemoration of Catrin’s life, but also as a memorial to all the women and children who have suffered in war.

Sources

Terry Breverton, Owain Glyndŵr: The Story of the Last Prince of Wales (Stroud, 2009).

Chris Given-Wilson (ed.), The Chronicle of Adam of Usk, 1377-1421 (Oxford, 1997).

J.E. Lloyd, Owen Glendower (Owain Glyn Dŵr) (Oxford, 1931).

Menna Elfyn, Murmur (Tarset, 2012).

I would also like to thank Sara Hanna-Black for her help and encouragement.

All images from Wikipedia

About the Author

David Santiuste teaches history at the Centre for Open Learning, University of Edinburgh. His most recent book is The Hammer of the Scots. His other publications include Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses, as well as various articles.

David Santiuste teaches history at the Centre for Open Learning, University of Edinburgh. His most recent book is The Hammer of the Scots. His other publications include Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses, as well as various articles.

David’s website can be found at davidsantiuste.com [insert link: https://davidsantiuste.com/], where he writes an occasional blog. You can follow him on Facebook at David Santiuste Historian or on Twitter @dbsantiuste.

The University of Edinburgh is a charitable body, registered in

Scotland, with registration number SC005336.

*

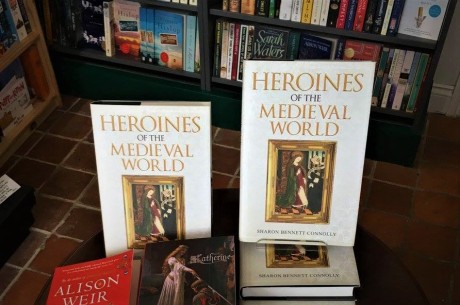

My Book:

Heroines of the Medieval World, is now available in hardback in the UK from both Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK. It is also available on Kindle in both the UK and USA and will be available in Hardback from Amazon US from 1 May 2018. It can also be ordered worldwide from Book Depository.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter.

*

©2018 Sharon Bennett Connolly

Reblogged this on Brittius.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

You’re welcome.

LikeLike

That’s fascinating – and intriguing. Despite my love of history (and, to a lesser extent, Shakespeare), I confess to not having heard of Catrin. I’ll keep an eye out for that statue next time I’m in the smoke!

Like

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLike

Sharon, your post is timely as I am reading a novel, Finding Camlaan, and Owain Glyn Dwr is part of the story. I had never heard of him (I am Peruvian) and I find the rebellions against the English occupants fascinating. Another interesting book is Fleeing Franco, an account of Basque children who were taken to Wales and placed into families so they were safe from the Generalissimo. The kindness of the Welsh towards these refugees was crucial in saving their lives.

LikeLike