In my research I frequently discover instances of happy medieval marriages – and even if a marriage was not based on love, it did not mean that it would not be successful. Indeed, in many such instances the young woman concerned found her own way of succeeding, whether it was through her children or the management of estates – or the fact that a lasting peace was achieved between her 2 countries.

Unfortunately for Joan of the Tower, later to be known as Joan Makepeace, her marriage achieved none of these things.

Joan was born in the Tower of London on 5 July, 1321; hence her rather dramatic name. She was the youngest of the 4 children of Edward II and his queen, Isabella of France, and had 2 older brothers and 1 sister. Her eldest brother, Edward, who was 9 years older than Joan, succeed his father as King Edward III in 1327, following Edward II’s deposition. While her 2nd brother, John of Eltham, was born in 1316 and died shortly after his 20th birthday, while campaigning against the Scots. Joan’s only sister, Eleanor of Woodstock, born in 1318, was only 3 years older than her baby sister and would go on to marry Reginald II, Count of Guelders.

Joan also had an illegitimate brother, Adam FitzRoy, a son of Edward II by an unknown woman. He was born in the early 1300s, but died whilst campaigning in Scotland with his father, in 1322.

Little Joan was named after her maternal grandmother, Queen Joan I of Navarre, wife of Philip IV of France. The king, also in London at the time of Joan’s birth, but not at the Tower, granted an £80 respite on a £180 loan to Robert Staunton, the man who brought him news of the birth.¹ By 8th July Edward was visiting his wife and baby daughter at the Tower of London and stayed with them for several days.

As the last of the children of Edward II and Isabella, it seems likely that the royal couple’s relationship changed shortly after her birth, their marriage heading for an irretrievable breakdown that would see the king deposed in favour of his son. Edward II was well known for having favourites; the first, Sir Piers Gaveston, met a sticky end in 1312, when he was murdered by barons angry at the influence he held over the king. Isabella’s estrangement with her husband followed the rise of a new favourite, Sir Hugh le Despenser, and, by the time of Joan’s birth, his influence on the king was gaining strength and alienating powerful barons at court. In March 1322 those barons were defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge, Yorkshire, with many prominent barons killed, including the king’s erstwhile brother-in-law Humphrey de Bohun, earl of Hereford. The leader of the insurrection, the king’s cousin Thomas, earl of Lancaster, was executed 6 days later at Pontefract Castle.

Joan was, therefore, growing up amid a period of great turmoil, not only within England, but within her own family. It is doubtful that, as she grew, she was unaware of the atmosphere, but Isabella and Edward were both loving parents and probably tried to shield their children as much as they could, ensuring stability in their everyday lives. Joan was soon placed in the household of her older siblings, and put into the care of Matilda Pyrie, who had once been nurse to her older brother, John of Eltham.

Sometime before February 1325, Joan and her sister were established in their own household, under the supervision of Isabel, Lady Hastings and her husband, Ralph Monthermer. Isabel was the younger sister of Edward II’s close companion, Hugh Despenser the Younger, and this act has often been seen by historians as the king removing the children from the queen’s custody. Although it could have been a malicious act it must be remembered, however, that Ralph Monthermer was the girls’ uncle-by-marriage through his first wife, Joan of Acre, Edward II’s sister, and it was a custom of the time that aristocratic children were fostered among the wider family.

Joan and her elder sister, Eleanor, remained with Isabel even after Ralph’s death in the summer of 1325; however, the following year, they were given into the custody of Joan Jermy, sister-in-law of the king’s younger half-brother Thomas, Earl of Norfolk. Joan was the sister of Thomas’s wife, Alice Hales, and took charge of the girls’ household in January 1326, living alternately at Pleshey in Essex and Marlborough in Wiltshire.

As with all her siblings, Joan played a part in her father’s diplomatic plans; an attempt to form an alliance against France, Edward sought marriages in Spain for 3 of his 4 children. While Eleanor was to marry Alfonso XI of Castile, little Joan was proposed as the bride for the grandson of Jaime II of Aragon – the future Pedro IV – but this would come to nought.

By this time their mother, Isabella, was living at the French court, along with her eldest son, Edward, refusing to return to her husband whilst he still welcomed Hugh Despenser at his court. Within months Isabella and her companion (possibly her lover), Roger Mortimer, were to invade England and drive Edward II from his throne, putting an end to the proposed Spanish marriages. He was captured and imprisoned in Berkley Castle, forced to abdicate in favour of his eldest son, who was proclaimed King Edward III in 1327.

With her father exiled or murdered (his fate remains a bone of contention to this day), Joan became the central part of another plan – that of peace with Scotland. Isabella and her chief ally, Roger Mortimer, were now effectively ruling the kingdom for the young Edward III – still only in his mid-teens. With the kingdom in disarray Isabella sought to end the interminable wars with Scotland, much to the young king’s disgust. Joan was offered as a bride for David, Robert the Bruce’s only son and heir, by his second wife, Elizabeth de Burgh.

The 1328 Treaty of Northampton was seen as a major humiliation by Edward III – and the 16-year-old king made sure his displeasure was known. However, he was forced to sign it, agreeing to Scotland’s recognition as an independent kingdom, the return of both the Ragman Roll (a document showing the individual acts of homage by the Scottish nobility) and the Stone of Scone (the traditional stone on which Scotland’s kings were crowned and which had sat in Westminster Abbey since being brought south by Edward I) and the marriage of Bruce’s 4-year-old son, David, to his 7-year-old sister, Joan.

Although the Stone of Scone and Ragman Roll were never returned to Scotland, the marriage between Joan and David did go ahead, although with a proviso that, should the marriage not be completed within 2 months of David reaching his 14th birthday, the treaty would be declared invalid. With neither king present – with Edward III refusing to attend, Robert the Bruce did likewise, claiming illness – the children were married at Berwick-on-Tweed on 17 July 1328, in the presence of Queen Isabella. The wedding was a lavish occasion, costing the Scots king over £2500.²

Following the wedding, and nicknamed Joan Makepeace by the Scots, Joan remained in Scotland with her child-groom. With Robert the Bruce’s death the following year, and David’s accession to the throne as David II, Joan and David attained the dubious record of being the youngest married monarchs in British history. They were crowned, jointly, at Scone Abbey in Perthshire, on 24th November 1331. It was the 1st time a Scottish Queen Consort was crowned.

Virtually nothing is known of Joan’s early years in Scotland. We can, I’m sure, assume she continued her education and maybe spent some time getting to know her husband. Scotland, however, was in turmoil and Edward III was not about to let his sister’s marriage get in the way of his own ambitions for the country. Unfortunately for Joan, Edward Balliol, son of the erstwhile king, John Balliol, and Isabella de Warenne, had a strong claim to the crown and was, as opposed to her young husband, a grown man with the backing of Edward III. What followed was a tug-of-war for Scotland’s crown, lasting many years.

David’s supporters suffered a heavy defeat at Halidon Hill in July 1333 and shortly after Joan, who was residing at Dumbarton at the time, and David were sent to France for their safety, where they spent the next 7 years. An ally of Scotland and first cousin of Joan’s mother, Philip VI of France gave the king and queen, and their Scottish attendants, accommodation in the famous Château Gaillard in Normandy.

Their return to Scotland, on 2nd June 1341, was greeted with widespread rejoicing that proved to be short-lived. When the French asked for help in their conflict with the English, David led his forces south. He fought valiantly in the disastrous battle at Neville’s Cross on 17th October 1346, but was captured by the English; he was escorted to a captivity in England that would last for the next 11 years, save for a short return to Scotland in 1351-52.

Joan and David’s marriage had proved to be an unhappy, loveless and childless union and, while a safe conduct was issued for Joan to visit her husband at Windsor for the St George’s Day celebrations of 1348, there is no evidence she took advantage of it. Although we know little of Joan’s movements, it seems she remained in Scotland at least some of the time, possibly held as a hostage to David’s safety by his Scottish allies. She may also have visited David in his captivity, taking it as an opportunity to visit with her own family, including her mother; Queen Isabella is said to have supported Joan financially while her husband was imprisoned, feeding and clothing her. Joan does not appear to have taken an active role in negotiations for David’s release, despite her close familial ties to the English court.

When David returned to Scotland he brought his lover, Katherine Mortimer, with him. They had met in England and it was said “The king loved her more than all other women, and on her account his queen was entirely neglected while he embraced his mistress.”³ Katherine met a grisly fate and was stabbed to death by the Earl of Atholl.

At Christmas 1357 Joan was issued with a safe conduct from Edward III “on business touching us and David” and again in May 1358 “by our licence for certain causes”.² Although the licences are understandably vague on the matter, Joan had, in fact, left David and Scotland.

Joan spent the rest of her life in England, living on a pension of £200 a year provided by her brother, Edward III. She renewed family connections and was able to visit her mother before Isabella’s death in August 1358. As Queen of Scotland, she occasionally acted on her husband’s behalf. In February 1359 David acknowledge her assistance in the respite of ransom payments granted by Edward III saying it was “at the great and diligent request and instance of our dear companion the Lady Joan his sister.”²

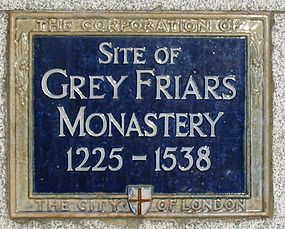

Little is known of Joan’s appearance or personality. Several years after her death she was described as “sweet, debonair, courteous, homely, pleasant and fair” by the chronicler Andrew of Wyntoun.² Having led an adventurous life, through no choice of her own, if unhappy in love, Joan of the Tower, Queen of Scotland, died at the age of 41 on 7th September 1362, and was buried in the Church of the Greyfriars, Newgate, in London, where her mother had been laid to rest just 4 years earlier.

Following his wife’s death David II married his lover, Margaret Drummond, the widow of Sir John Logie, but divorced her on 20th March 1370. He died, childless, at Edinburgh Castle in February 1371, aged 47, and was succeeded by the first of the Stewart kings, his nephew, Robert II, son of Robert the Bruce’s eldest daughter, Marjorie.

*

Footnotes: ¹Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen by Kathryn Warner; ² Oxforddnb.com; ³Walter Bower quoted in Oxforddnb.com

Sources: The Story of Scotland by Nigel Tranter; Brewer’s British Royalty by David Williamson; Kings & Queens of Britain by Joyce Marlow; Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens by Mike Ashley; Oxford Companion to British History Edited by John Cannon; Britain’s Royal Families by Alison Weir; educationscotland.gov.uk/scotlandhistory; englishmonarchs.co.uk; berkshirehistory.com; thefreelancehistorywriter.com; The Perfect King by Ian Mortimer; Scotland, History of a Nation by David Ross; The Life & Times of Edward III by Paul Johnson; The Reign of Edward III by W.M. Ormrod; Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen by Kathryn Warner; Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II by Paul Doherty; Edward II: The Unconventional King by Kathryn Warner; Oxforddnb.com.

*

My Books

Signed, dedicated copies of all my books are available, please get in touch by completing the contact me form.

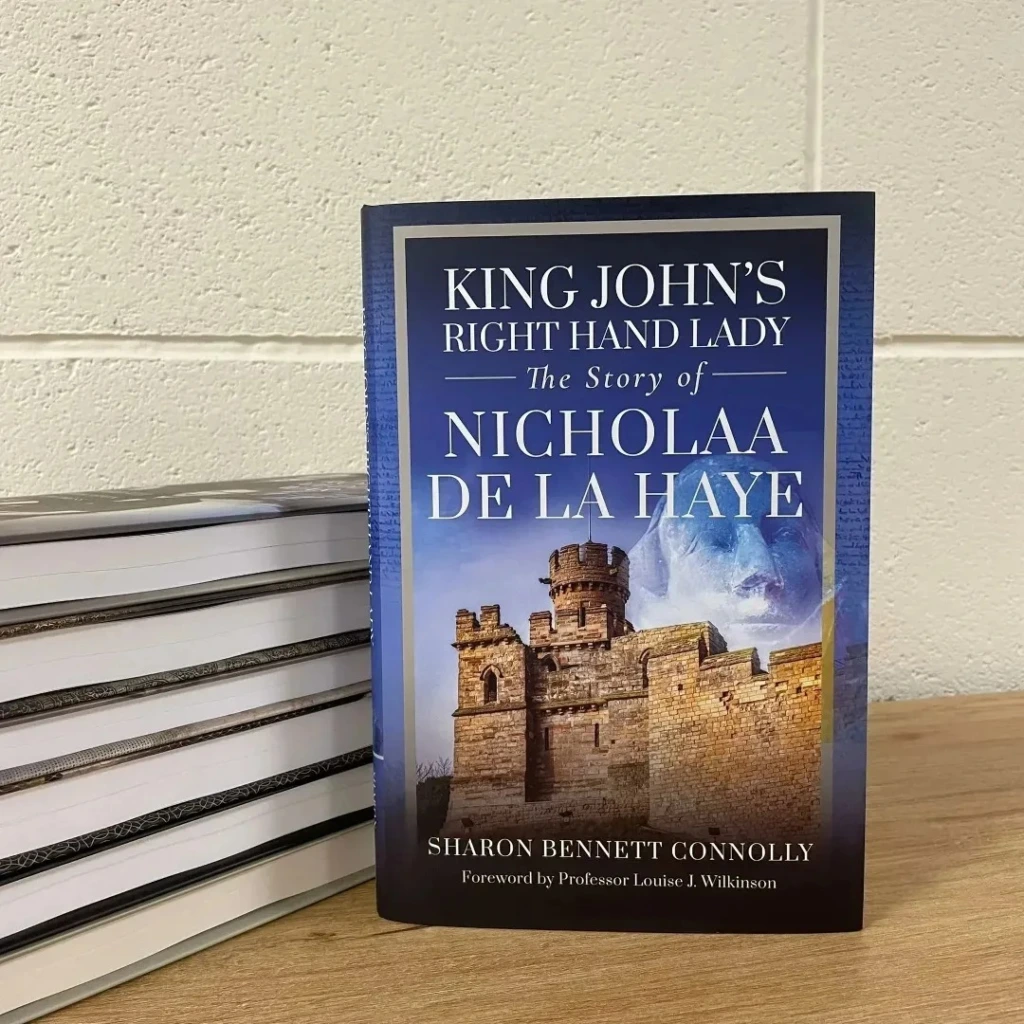

Out now: King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye

In a time when men fought and women stayed home, Nicholaa de la Haye held Lincoln Castle against all-comers, gaining prominence in the First Baron’s War, the civil war that followed the sealing of Magna Carta in 1215. A truly remarkable lady, Nicholaa was the first woman to be appointed sheriff in her own right. Her strength and tenacity saved England at one of the lowest points in its history. Nicholaa de la Haye is one woman in English history whose story needs to be told…

King John’s Right-Hand Lady: The Story of Nicholaa de la Haye is now available from Pen & Sword Books, bookshop.org and Amazon.

Coming 15 January 2024: Women of the Anarchy

On the one side is Empress Matilda, or Maud. The sole surviving legitimate child of Henry I, she is fighting for her birthright and that of her children. On the other side is her cousin, Queen Matilda, supporting her husband, King Stephen, and fighting to see her own son inherit the English crown. Both women are granddaughters of St Margaret, Queen of Scotland and descendants of Alfred the Great of Wessex. Women of the Anarchy demonstrates how these women, unable to wield a sword, were prime movers in this time of conflict and lawlessness. It show how their strengths, weaknesses, and personal ambitions swung the fortunes of war one way – and then the other.

Available for pre-order from Amberley Publishing and Amazon UK.

Also by Sharon Bennett Connolly:

Defenders of the Norman Crown: The Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey tells the fascinating story of the Warenne dynasty, from its origins in Normandy, through the Conquest, Magna Carta, the wars and marriages that led to its ultimate demise in the reign of Edward III. It is now available from Pen & Sword Books, Amazon in the UK and US, and Bookshop.org.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England looks into the relationships of the various noble families of the 13th century, and how they were affected by the Barons’ Wars, Magna Carta and its aftermath; the bonds that were formed and those that were broken. It is now available in paperback and hardback from Pen & Sword, Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Heroines of the Medieval World tells the stories of some of the most remarkable women from Medieval history, from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Julian of Norwich. Available now from Amberley Publishing and Amazon, and Bookshop.org.

Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest traces the fortunes of the women who had a significant role to play in the momentous events of 1066. Available now from Amazon, Amberley Publishing, and Bookshop.org.

Alternate Endings: An anthology of historical fiction short stories including Long Live the King… which is my take what might have happened had King John not died in October 1216. Available in paperback and kindle from Amazon.

Podcast:

Have a listen to the A Slice of Medieval podcast, which I co-host with Historical fiction novelist Derek Birks. Derek and I welcome guests, such as Bernard Cornwell and discuss a wide range of topics in medieval history, from significant events to the personalities involved.

*

For forthcoming online and in-person talks, please check out my Events Page.

You can be the first to read new articles by clicking the ‘Follow’ button, liking our Facebook page or joining me on Twitter and Instagram.

©2017 Sharon Bennett Connolly FRHistS

Reblogged this on Brittius.

LikeLike

Thank you – appreciate it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Marie Macpherson.

LikeLike

Thank you – appreciate it. 🙂

LikeLike

I’m inclined to think there were more happy, or at least contented and successful Medieval marriages than we sometimes think. Of course, I am also of the opinion, that, contrary to the depiction in fiction, Aethelflead Lady of the Mercians was content in her marriage to Lord Ethelred……all that silliness about Viking lovers. Tsk.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Marriage was certainly not as one-sided, male-orientated a state as has been depicted. Women found ways to feel satisfied and accomplished, either in estate management, philanthropy or raising children. I don’t think medieval women were feminists – not even Eleanor of Aquitaine – but the majority of them did find many ways to fulfill their lives (which is, hopefully what my book will show 😉 ).

I think of Aethelflaed as having no need lovers. I tend to think of her dedicated to uniting England. 🙂

LikeLike

Well, the sources suggest that she was in charge, at intervals, from 906, and perhaps earlier. So she was playing an active role in the defense of her Kingdom, raising her daughter and later her nephew, and there is evidence that she was Literate (I like to think she read some of the books her father had sent to the Mercian court).

So there was plenty to keep her fulfilled, but don’t want to give away too much of course.

LikeLike

I know! It’s at the top of my reading pile. Reading Michael Jones’ book on the Black Prince, then yours is up. 🙂

I haven’t got my notes to hand, but I did read one suggestion that she’d taken a vow of celibacy after Aelfwyn’s birth – and I like that idea.

LikeLike

Oh, is that one available for review. Print or PDF? If its Print I am so asking for a copy.

The reference to the vow of celibacy is from William of Malmesbury.

LikeLike

Print. Just waiting for the proof copy to do the final edit. Out in September. ☺

LikeLike

Oh. I could have done with more editing on mine. Lot of typos got through.

LikeLike

Right, wrong, good or bad… Piers was my Ancestor.

Thank you for one of easiest stories to that complicated time.

LikeLike

Thank you Kristie, glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on History's Untold Treasures and commented:

History…The Interesting Bits

LikeLike

Thank you ☺

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome!

LikeLike

A good and very interesting read thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Sam 😀

LikeLike